Realism and Naturalism in America

Writer/performer/manager Dion Boucicault (1822-1890) wrote increasingly realistic melodramas, including The Poor of New York, an outright steal of The Poor of Paris, but set firmly in America,

framed by the financial panics of 1837 and 1857. The Octoroon; or, Life in Louisiana is about a woman white enough to “pass” but who is discovered to be black and suffers the consequences. Boucicault was so popular a writer that he could and did demand royalties, which have become a playwright’s bread and butter (well, before they could sell the movie rights!). Before Boucicault’s lobbying for royalties and living wages for writers, a very popular nautical melodrama, Jerrold’s Black-Eyed Susan, earned its author a paltry 70 pounds. Boucicault earned over 500,000 pounds on the royalties for only one of his plays. Rigorous international copyright laws did not go into effect until just after the turn of the 20th century, but Boucicault really paved the way in securing rights and money for writers. Boucicault is also usually credited with responsibility for the long run as the usual way to do theatre in the States. Because his plays were SO popular, they no longer had to be run in rotating rep with other plays. His plays could run on their own for weeks, months, years. Uncle Tom’s Cabin predates Boucicault’s plays in this, but it was the exception, not the rule.

After the Civil War in America, then, more and more often single

plays began to be run in New York City, the center of theatrical activity, and

then tour the country, not via troupes of traveling players who would

incorporate it into their rotating rep, but lock stock and barrel, in what was

known as a combination company – one

that takes everything needed (actors, sets and costumes, technicians) to do a

single play. The rapidly constructed new railroads which began to

criss-cross the US in the 1860s and 70s allowed for this new way of doing

theatre: run a play in NYC as long as financially feasible, then send it out on

national tours. So this collusion of very successful single plays (it’s

much easier and cheaper to tour a single play rather than a repertoire of plays)

and the extraordinary transportation revolution created by the proliferation of

railroads was a major factor in changing the way theatre was delivered. To give

you some sense of the scope of this, by the theatrical season of 1876-77 there

were nearly 100 touring companies on the (rail)road. By 1886-87 the number of

touring companies in the US had nearly tripled, to 282!

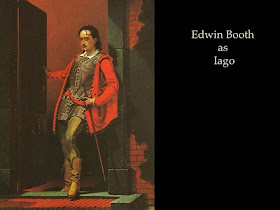

One of the earliest of these “long run” plays was the Hamlet of Edwin Booth (1833-1893), which ran for 100 nights. Although his

brother John Wilkes nearly killed his brother’s career the night he assassinated Lincoln, Edwin went into seclusion but re-emerged in less than a year and rapidly became the greatest actor-manager in American theatre in the latter half of the 19th century. The 100-Nights Hamlet really launched Booth’s career. As an actor Booth believed that the theatre artists should perform only the finest drama, and that it was the actor’s job to bring out the beauty and wisdom in the play. In Edwin Booth, then, we see one of the first (and nearly ONLY) argument for an “art” theatre in America.

brother John Wilkes nearly killed his brother’s career the night he assassinated Lincoln, Edwin went into seclusion but re-emerged in less than a year and rapidly became the greatest actor-manager in American theatre in the latter half of the 19th century. The 100-Nights Hamlet really launched Booth’s career. As an actor Booth believed that the theatre artists should perform only the finest drama, and that it was the actor’s job to bring out the beauty and wisdom in the play. In Edwin Booth, then, we see one of the first (and nearly ONLY) argument for an “art” theatre in America.

Booth also ventured into new experiments with stage

architecture. In his own theatre, called Booth’s and opened in 1869,

Booth got

rid of the raked stage and introduced “free plantation” style sets. These consisted of large set pieces and flats not dependent on painted side wings, but “planted” in different parts of the stage. These set pieces could be flown from above or raised from below on the elevators he installed. The free plantation system created a more realistic look on stage, and Booth often used box sets in his plays for still greater scenic realism.

rid of the raked stage and introduced “free plantation” style sets. These consisted of large set pieces and flats not dependent on painted side wings, but “planted” in different parts of the stage. These set pieces could be flown from above or raised from below on the elevators he installed. The free plantation system created a more realistic look on stage, and Booth often used box sets in his plays for still greater scenic realism.

Edwin Booth was certainly the most important American

actor-manager at this time, but another is worth mentioning, because in

what was almost exclusively a man’s domain, Laura Keene (1820-1893) was, obviously, a woman! Keene battled from the 1850s to the 1870s, to secure her own theatre in competition with several males, most of whom wanted to destroy her merely because she was a woman. She became tremendously popular in spite of all sorts of hardships. Keene used to be known only as the star of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre the night Lincoln was shot, but more recently, Keene has become a landmark example of American women actor managers -- she was hardly the only one, and not the first, but one of the most important.

what was almost exclusively a man’s domain, Laura Keene (1820-1893) was, obviously, a woman! Keene battled from the 1850s to the 1870s, to secure her own theatre in competition with several males, most of whom wanted to destroy her merely because she was a woman. She became tremendously popular in spite of all sorts of hardships. Keene used to be known only as the star of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre the night Lincoln was shot, but more recently, Keene has become a landmark example of American women actor managers -- she was hardly the only one, and not the first, but one of the most important.

Two men deserve attention at this time because they ran theatres,

directed actors, and wrote plays but did NOT star in them. In breaking

from the actor/manager tradition, Augustin Daly and David Belasco became two of

the earliest professional directors

in American (or any other) theatre. Augustin

Daly (1836-1899)

was quite a hustler. He wrote drama criticism under assumed names for 5 different newspapers in NYC. While it was not unusual to write under a nom de plume, it was unusual to write for so many papers, and to critique plays while producing your own plays. A Daly play opens, and 5 papers automatically love it! This interesting take on self promotion didn’t last for long, and much more importantly, Daly was a major contributor to stage realism,

not in his stories, which were totally melodramatic. It was Daly’s idea, for example, to tie a person to a railroad track to gain suspense in a play called Under the Gaslight. But he was realistic in his staging techniques. In his production of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, for example, Daly’s scene painters reproduced precise renderings of famous sites in the title

city. In his Midsummer

Night’s Dream, fifth century BC Athens was re-created as closely as

possible on the stage. Daly was also

crucial in the development of the professional director in that he insisted

upon absolute control over all elements of production. He wooed the best

actors in America to his company, including Clara Morris,

who, because she was so fine at pathetic suffering, was known as the “queen of spasms” and John Drew II, a fine leading man, and one of the earliest of the line which became the Barrymore family. Drew played leading roles opposite Ada Rehan, as Petruchio to her Kate for example. Rehan became Daly’s favorite -- in fact she became his mistress! And while Daly otherwise insisted on the importance of ensemble playing, he made Ada Rehan a star.

was quite a hustler. He wrote drama criticism under assumed names for 5 different newspapers in NYC. While it was not unusual to write under a nom de plume, it was unusual to write for so many papers, and to critique plays while producing your own plays. A Daly play opens, and 5 papers automatically love it! This interesting take on self promotion didn’t last for long, and much more importantly, Daly was a major contributor to stage realism,

not in his stories, which were totally melodramatic. It was Daly’s idea, for example, to tie a person to a railroad track to gain suspense in a play called Under the Gaslight. But he was realistic in his staging techniques. In his production of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, for example, Daly’s scene painters reproduced precise renderings of famous sites in the title

|

| Hisstorical accuracy at the expense of the play? |

who, because she was so fine at pathetic suffering, was known as the “queen of spasms” and John Drew II, a fine leading man, and one of the earliest of the line which became the Barrymore family. Drew played leading roles opposite Ada Rehan, as Petruchio to her Kate for example. Rehan became Daly’s favorite -- in fact she became his mistress! And while Daly otherwise insisted on the importance of ensemble playing, he made Ada Rehan a star.

If Daly was known for realistic staging, David Belasco (1854-1931) became famous for stage naturalism. At

the same time that

Andre Antoine was directing naturalist drama on stage in Paris, Belasco was doing it in New York. Belasco wrote many of the plays he produced, including Heart of Maryland (1895) in which a daughter saves her father from execution by hanging on the clapper of the bell that is to ring in the hour of his death. You've heard of "cliff-hangers..Maryland is the first (and I hope only) bell-hanger! Two other of his plays, Madame Butterfly (1900) and Girl of the Golden West

(1905), were operatized by Puccini and are much better known as operas – melodramatic? Nooooo! But Belasco is best remembered for his staging. When he directed Eugene Walters’ grittily naturalistic The Easiest Way (1909), Belasco, he needed a cheap boardinghouse room for his main character (a prostitute who could have broken away from her awful existence by marrying a reporter who loved her, but who instead took the “easiest way” and remained in her trade), so he merely bought an entire boardinghouse in the infamous “tenderloin” district of Manhattan and put what he needed of it on the stage. In the Governor’s Lady there was a scene set in a restaurant. Belasco bought one of the Child’s chain of restaurants and simply placed it on the stage! Belasco was also a flamboyant producer and star-maker, one of the great early American directors.

Andre Antoine was directing naturalist drama on stage in Paris, Belasco was doing it in New York. Belasco wrote many of the plays he produced, including Heart of Maryland (1895) in which a daughter saves her father from execution by hanging on the clapper of the bell that is to ring in the hour of his death. You've heard of "cliff-hangers..Maryland is the first (and I hope only) bell-hanger! Two other of his plays, Madame Butterfly (1900) and Girl of the Golden West

(1905), were operatized by Puccini and are much better known as operas – melodramatic? Nooooo! But Belasco is best remembered for his staging. When he directed Eugene Walters’ grittily naturalistic The Easiest Way (1909), Belasco, he needed a cheap boardinghouse room for his main character (a prostitute who could have broken away from her awful existence by marrying a reporter who loved her, but who instead took the “easiest way” and remained in her trade), so he merely bought an entire boardinghouse in the infamous “tenderloin” district of Manhattan and put what he needed of it on the stage. In the Governor’s Lady there was a scene set in a restaurant. Belasco bought one of the Child’s chain of restaurants and simply placed it on the stage! Belasco was also a flamboyant producer and star-maker, one of the great early American directors.

Another early director was Steele

MacKaye (1842-1894), also an actor, playwright, & inventor.

MacKaye brought Delsarte’s system

of performance training to America and started one of the earliest acting schools in the U.S., which would later become the American Academy of Dramatic Art. He wrote very realistic melodramas, including Marriage (1869) and Hazel Kirke (1878). The realism in these plays was more in the staging than in the story. MacKaye was an idealist, and started several theatres. Along with Booth, MacKaye was one of the few who advocated for art in the nineteenth century American theatre, where the dollar was almighty. Unfortunately, MacKaye’s idealism lost him lots of money, but this did not stop him from experimenting and inventing.

He came up with an early form of air conditioning a theatre auditorium (huge blocks of ice placed just out of sight, blown by large fans to cool a theatre on a hot summer’s night). He used huge elevators for quicker set changes. It was usual at the time to listen to music during set changes, with hammers banging in the background, for 5-10 minutes between scenes. MacKaye’s elevator system cut the time it took to change even complicated scenes to 40 seconds. MacKaye was also one of the first directors to see the potential of and to use electric light in the theatre.

of performance training to America and started one of the earliest acting schools in the U.S., which would later become the American Academy of Dramatic Art. He wrote very realistic melodramas, including Marriage (1869) and Hazel Kirke (1878). The realism in these plays was more in the staging than in the story. MacKaye was an idealist, and started several theatres. Along with Booth, MacKaye was one of the few who advocated for art in the nineteenth century American theatre, where the dollar was almighty. Unfortunately, MacKaye’s idealism lost him lots of money, but this did not stop him from experimenting and inventing.

He came up with an early form of air conditioning a theatre auditorium (huge blocks of ice placed just out of sight, blown by large fans to cool a theatre on a hot summer’s night). He used huge elevators for quicker set changes. It was usual at the time to listen to music during set changes, with hammers banging in the background, for 5-10 minutes between scenes. MacKaye’s elevator system cut the time it took to change even complicated scenes to 40 seconds. MacKaye was also one of the first directors to see the potential of and to use electric light in the theatre.

It is at this time that America’s unique gift to world theatre,

the musical, was born. In 1866

a melodrama was in its final stages of rehearsal, but James Niblo, manager of

Niblo’s Garden’s Theatre, saw that it was in major trouble. It was

missing...something!

Meanwhile, nearby in Manhattan, another theatre has burned down, leaving a troupe of French female dancers nowhere to play. The answer? Niblo decided to combine forces with the dance troupe, and accidentally created what is usually called the first American musical, The Black Crook. Granted, most melodramas made use of music, but this was something else, and the formula Niblo stumbled on out of necessity created a sensation. Niblo had great settings (the play was a fantasy, in which a magician is constantly transforming things, making use of lots of sets and set changes) and a pretty crummy story. But when the dancing girls arrived, he realized he didn’t really NEED a story. He

had a chorus line of lovely legs! This combination of spectacle and cheesecake proved a huge success. The Black Crook was a hit! The next year another foreign troupe, Lydia Bailey and her British Blondes, took New York by storm in a similar manner. After these two experiments, in 1874 Evangeline hit the stage. Based VERY loosely upon a Longfellow poem, this

show featured

scantily clad dancers, a whale and a dancing heifer (two men in a cow-costume),

along with songs such as “In Love with the Man in the Moon.” Despite the

critics, one of whom wrote of it: “Several scenes are so

stupid, that it is difficult to contemplate them without going to sleep,” Evangeline became hugely popular and others like

it began to be written. Audiences began to get a steady stream of these new

musical entertainments, and little changed in the format of the American

musical until December 1927...but more of that later!

Meanwhile, nearby in Manhattan, another theatre has burned down, leaving a troupe of French female dancers nowhere to play. The answer? Niblo decided to combine forces with the dance troupe, and accidentally created what is usually called the first American musical, The Black Crook. Granted, most melodramas made use of music, but this was something else, and the formula Niblo stumbled on out of necessity created a sensation. Niblo had great settings (the play was a fantasy, in which a magician is constantly transforming things, making use of lots of sets and set changes) and a pretty crummy story. But when the dancing girls arrived, he realized he didn’t really NEED a story. He

had a chorus line of lovely legs! This combination of spectacle and cheesecake proved a huge success. The Black Crook was a hit! The next year another foreign troupe, Lydia Bailey and her British Blondes, took New York by storm in a similar manner. After these two experiments, in 1874 Evangeline hit the stage. Based VERY loosely upon a Longfellow poem, this

|

| Evangeline? |

Quick

sidebar: for a great description of Evangeline

have a look at this website from the New York Public Library: http://www.nypl.org/blog/2012/11/30/musical-month-evangeline

If you move towards scantily clad women and away from a

well-plotted play, you get burlesque

American style -- a collection of variety acts and musical numbers in which

women “take off”, not in the sense of mocking other forms, but in the sense of

their clothes! Tony Pastor cleaned up the burlesque around the turn of

the century, made it suitable for the entire family, usually, and called it

vaudeville, which was a hugely successful form until the talking pictures began

stealing its audiences away.

There were many famous actors working in the U.S. at this time,

and several of them I’ve already mentioned. Let’s look quickly at three more: William Gillette was a major star in the 1890s, and wrote plays as vehicles for himself, including Secret Service (1892) and Sherlock Holmes (1895). He was a highly realistic actor. It was Gillette who first said that every night an actor plays, s/he should attempt to present “the illusion of the first time.”

and several of them I’ve already mentioned. Let’s look quickly at three more: William Gillette was a major star in the 1890s, and wrote plays as vehicles for himself, including Secret Service (1892) and Sherlock Holmes (1895). He was a highly realistic actor. It was Gillette who first said that every night an actor plays, s/he should attempt to present “the illusion of the first time.”

James O’Neill was an actor

who had played Othello to Edwin Booth’s Iago, but then got sucked into a play

version of The Count of Monte Cristo,

which he toured everywhere, which he made tons of money from, and which nearly

destroyed his family...read his son’ Eugene’s play on the subject, Long Day’s Journey into Night.

Finally, Richard Mansfield,

star of melodrama (Beau Brummel),

dabbler in Shakespearean roles (Richard III probably best among them), introducer of Shaw to America (Arms and the Man, Devil’s Disciple) -- he toured England and flopped there, but was probably the most popular actor in America in the 1890s. The man he tried to emulate was the most famous actor in England at the time -- Henry Irving. And this brings us briefly to England.

dabbler in Shakespearean roles (Richard III probably best among them), introducer of Shaw to America (Arms and the Man, Devil’s Disciple) -- he toured England and flopped there, but was probably the most popular actor in America in the 1890s. The man he tried to emulate was the most famous actor in England at the time -- Henry Irving. And this brings us briefly to England.

Quick Look at Late Nineteenth Century British Theatre

Henry Irving was the

undisputed star of the London stage at the end of the century. In fact British

theatre at the end of the century

has been referred to as the age of Irving – this means that not only was he the greatest actor of his age, but also that he typifies the period. Irving began his career in 1871 as a player of leading roles at the Lyceum, a theatre he remained associated with all his life. In 1878, Irving took over management of the Lyceum, where he strove for pictorial realism. As Booth had done in America,

Irving ripped out the wings and grooves on the stage, replaced the raked floor with a flat floor -- the stage was equipped with flies that sent scenery in from above and elevators that lifted it from below, all in the service of free plantation of the scenery. Irving’s repertoire featured a traditional mix of Shakespeare and melodrama, but he used modern staging methods to produce the plays. Irving was knighted in 1895, the first actor in England to be knighted, and as important as it was for Irving, it also marked a new respect for at least some actors in England.

has been referred to as the age of Irving – this means that not only was he the greatest actor of his age, but also that he typifies the period. Irving began his career in 1871 as a player of leading roles at the Lyceum, a theatre he remained associated with all his life. In 1878, Irving took over management of the Lyceum, where he strove for pictorial realism. As Booth had done in America,

Irving ripped out the wings and grooves on the stage, replaced the raked floor with a flat floor -- the stage was equipped with flies that sent scenery in from above and elevators that lifted it from below, all in the service of free plantation of the scenery. Irving’s repertoire featured a traditional mix of Shakespeare and melodrama, but he used modern staging methods to produce the plays. Irving was knighted in 1895, the first actor in England to be knighted, and as important as it was for Irving, it also marked a new respect for at least some actors in England.

Irving’s leading lady, and surely the most popular actress in

London during the late 19th century, was Ellen Terry. She came from

a

theatrical family; her sister Kate, for example, also had a fine career, her

son was Gordon Craig, about whom we’ll speak next week, and her grandson was

John Gielgud! Terry excelled at Shakespearean comedy, particularly in the

roles of Beatrice, Viola, and Portia; but she was also quite fine in serious

roles, such as Lady Macbeth. She was made the first Dame (which is somewhat equivalent

to knighthood for women), shortly after Irving was knighted.

A rather unique contribution to musical theatre was created in

late

nineteenth century London by William Gilbert (1836-1911) and Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900), who wrote a series of satirical comic operettas for the Savoy Theatre between the mid-1870s and the mid-1890s. The operettas of Gilbert and Sullivan, which include HMS Pinafore (1878), The Pirates of Penzance (1879), and The Mikado (1885), remain staples of that genre today and are still frequently performed.

nineteenth century London by William Gilbert (1836-1911) and Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900), who wrote a series of satirical comic operettas for the Savoy Theatre between the mid-1870s and the mid-1890s. The operettas of Gilbert and Sullivan, which include HMS Pinafore (1878), The Pirates of Penzance (1879), and The Mikado (1885), remain staples of that genre today and are still frequently performed.

At the turn of the century, actor/manager Herbert Beerbohm-Tree (1853-1917) was one of the most important performers

and also

one the last of the great actor/managers. Beerbohm-Tree offered audiences Shakespeare the old fashioned way, and played many of the Bard’s great comic as well as serious roles. His production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream featured live rabbits in a super-realistic forest. The star’s greatest success came in 1916 when he offered a London public in dire need of escape from the ugly fact of the First World War a musical extravaganza called Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, which ran for 2,000 performances, the longest running show to that date in London. Beerbohm-Tree also originated the role of Henry Higgins for George Bernard Shaw in Pygmalion. This places him at a strategic moment while extravaganzas were popular, but while other new theatrical styles were ushering in the modern era.

one the last of the great actor/managers. Beerbohm-Tree offered audiences Shakespeare the old fashioned way, and played many of the Bard’s great comic as well as serious roles. His production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream featured live rabbits in a super-realistic forest. The star’s greatest success came in 1916 when he offered a London public in dire need of escape from the ugly fact of the First World War a musical extravaganza called Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, which ran for 2,000 performances, the longest running show to that date in London. Beerbohm-Tree also originated the role of Henry Higgins for George Bernard Shaw in Pygmalion. This places him at a strategic moment while extravaganzas were popular, but while other new theatrical styles were ushering in the modern era.

In terms of theatre spaces in Europe, England and the U.S.,

towards the end of the century as realism became more and more THE trend,

theatres in England became more and more complicated backstage and became

somewhat more intimate. Mainstream theatres built at the end of the 19th

century began to abandon the pit, box, and gallery system for the orchestra (or

stalls, or parterre) and balcony system we’re used to today on Broadway. In

fact the first theatres built around 42nd Street in NYC were built at the

turn of the century. The usual seating capacity went down from 2,000-3,000

seats to 1000-1500 seats. For example, the New Amsterdam, built in the early

years of the 20th century, seats a bit over 1700.

In recent lectures I’ve simplified a highly complex time period.

Mainstream theatre featured realistic dramas, but various anti-realistic

theatrical movements were growing as well. It gets more complicated as we

move forward, but in order to do that will now move back a bit in time, to

writers, directors, designers, who began to experiment with form that we have labeled the “modern.”