Most scholars consider private theatres quite similar to the public theatres in terms of stage and scenic elements. The King’s Men,

As the private theatres were indoors, they had to be artificially

lit, by candles. While plays at public theatres ran without

intermission, it was necessary to create intermissions in private houses, as the candle wicks had to be trimmed regularly. There were two galleries around three quarters of the stage, some of which were divided into boxes; and there was the pit, as well, but with a difference. Instead of standing room only, there were rows of backless benches, and seats in the rows near the stage were among the highest priced in the theatre. The stage was very like that of a public theatre, with some sort of second level, some sort of discovery space, a trap, two doors on the back wall for entrances and exits.

intermission, it was necessary to create intermissions in private houses, as the candle wicks had to be trimmed regularly. There were two galleries around three quarters of the stage, some of which were divided into boxes; and there was the pit, as well, but with a difference. Instead of standing room only, there were rows of backless benches, and seats in the rows near the stage were among the highest priced in the theatre. The stage was very like that of a public theatre, with some sort of second level, some sort of discovery space, a trap, two doors on the back wall for entrances and exits.

Another very important difference was the location of the private

theatres. Unlike the public theatres, which had to be located

outside the city’s boundaries, the private theatres were located IN the city of London, in spite of constant complaints and railing from town officials like the Lord Mayor wanted all the theatres closed, attacking them as gathering places for “all vagrant persons and masterless men that hang about the city, thieves, horse stealers, whoremongers, cozeners, coneycatchers, practicers of treason and other such like;” and from other concerned citizens, who asked: “do [theatres] not induce whoredom and uncleanness, and renew the remembrance of heathen idolatry? Nay, are they not plain devourers of maidenly virginity and chastity...?”

outside the city’s boundaries, the private theatres were located IN the city of London, in spite of constant complaints and railing from town officials like the Lord Mayor wanted all the theatres closed, attacking them as gathering places for “all vagrant persons and masterless men that hang about the city, thieves, horse stealers, whoremongers, cozeners, coneycatchers, practicers of treason and other such like;” and from other concerned citizens, who asked: “do [theatres] not induce whoredom and uncleanness, and renew the remembrance of heathen idolatry? Nay, are they not plain devourers of maidenly virginity and chastity...?”

With all this ill feeling from the mayor and his friends, how did

private theatres get to locate in the city? Well, they were built in

areas called “liberties,” lands that had been used for Catholic

monasteries

before Henry VIII confiscated them in 1539. In Elizabeth’s day the crown

was much friendlier to the theatre than was the increasingly Puritanical moral

majority. Two principal liberties in London were named Blackfriars and

Whitefriars, for the orders of monks who lived there before the

confiscation. The first theatre in Blackfriars was built in 1576, the

same year that The Theatre opened its doors, and the occupants were a company

of schoolboys, who performed school plays, and enjoyed amateur status.

Theatre done in schools for educational purposes was often condoned in places

that condemned professional theatre. These boys’ troupes became

very popular (and lucrative for the adults who ran them!), often

competing successfully against the adult troupes.

|

| As close as we can get to an exact location for Blackfriars Playhouse, in the heart of the City of London |

In 1596, James Burbage wanted a piece of this indoor action, and

bought at great expense the Blackfriars space, built a new, 2nd Blackfriars

theatre, and prepared to open. But the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were not allowed

to play there. Many powerful people lived in that area and petitioned the crown

that liberty or not, professional actors and the undesirables they brought into

a theatre had no place in this part of town...very ironically, one of the men

who signed the petition was the Lord Chamberlain! Some scholars think

that Burbage never recovered from this, and in fact he died in less than a

year. He willed the space to his sons, and all they could do with it was

lease it to a boys’ company.

Andrew Gurr, one of the most respected and knowledgeable recent

scholars of Shakespearean production, is convinced that it was in the indoor

Blackfriars that Burbage planned to make the kind of money he realized he could

with an indoor theatre, and that the Globe was an afterthought. Indeed,

it became pretty clear after the adult troupes were finally allowed to play

inside the city, in 1610, that the shareholders of the King’s men much

preferred the indoor theatre, where they were able to make over double what

they made outdoors. After 1610 they usually played from mid-October to

mid-May at Blackfriars and only in the summer months back at the Globe.

Soon after, other adult companies acquired private theatres, including the

Cockpit at Drury lane and the Cockpit at Court. So a trend towards indoor

theatres in England begins with the Jacobean era.

Let’s now look at scenery, costumes, audiences and actors.

We know a good bit about set pieces

that could be thrust out, lowered or raised onto the main stage in a public or

private theatre from the

account books of the Master of Revels, who noted what scenery was needed whenever plays were performed at court, and from Philip Henslowe’s meticulous records, As you read the main items from Henslowe’s notes, keep in mind that the idea of scenery was much as it had been in medieval English theatre: mansion and platea, set pieces emblematic rather than specific (chair = throne, for example) and playing space established around a mansion. Establishing a platea would be particularly important, for example, when two armies occupied the same stage. With that in mind, here is a selection from Henslowe’s inventory of set pieces:

account books of the Master of Revels, who noted what scenery was needed whenever plays were performed at court, and from Philip Henslowe’s meticulous records, As you read the main items from Henslowe’s notes, keep in mind that the idea of scenery was much as it had been in medieval English theatre: mansion and platea, set pieces emblematic rather than specific (chair = throne, for example) and playing space established around a mansion. Establishing a platea would be particularly important, for example, when two armies occupied the same stage. With that in mind, here is a selection from Henslowe’s inventory of set pieces:

3 trees

2 mossy banks

2 tombs

2 steeples

a hell-mouth

a chariot

a bed

a painted cloth showing Rome

Another important source of scenery is the text, in two

senses: first, a close reading of the text tells us what an actor needs

to have: I love this example from Midsummer:

“all I know is this bush is my bush, this lantern is my lantern, and this

dog...is my dog!” And second, much of the scenic effect in Shakespeare comes

from what we call “spoken decor:” as in ancient Greece the words tell us where

we are and sometimes when we are there. A group of actors walks out onto a bare

stage and one says, “This castle hath a pleasant seat.” We know where we

are. Hamlet walks out into the afternoon sun, and says, “’Tis now the

very witching hour of night.” We know what time it is.

Costumes?

Contemporary Elizabethan dress, for the most part, sometimes bought, sometimes

handed down from nobles. But there were special costumes.

1) In ancient plays, usually Roman or Greek, a piece of

ancient-style garment was laid over an other wise Elizabethan outfit; there’s

an interesting example of this in Henry Peacham’s 1595 drawing of costumes for what

is almost surely Titus Andronicus.

2)

Characters from English tradition, such as Robin Hood, could be identified by special

outfits.

3) Fanciful garments might be worn by ghosts and especially fairies

and sprites.

4) Racial costumes to indicate Turks and Jews; for example, Shylock

speaks of his “Jewish gabardine” and he also wore an oversize, hooked nose.

Elizabethan audiences

came from all classes to these theatres, and they came in droves. A study

indicates that during the height of the outdoor theatres approximately 21,000

people a week attended the theatre, from an overall London population, or about

1 in 8, a rate, claims scholar Bamber Gascoigne, not equalled except in

London’s cinema houses between WWI and WWII.

And there were all kinds among those classes. We’ve

mentioned the gallants showing off their large plumed hats on stage. At the

other end of the economic scale were the “groundlings” who paid one penny to

stand in the yard. By the way it was tremendously fashionable to smoke tobacco

in this era, and you can bet there was a lot of pipe smoking going on. That at

least that would have covered some of the less pleasant smells at the playhouse,

one hopes. Perhaps the groundlings got it right, as they stood under the

open sky and may have been able to breathe more freely than those in more

expensive seats. We know from the Lord Mayor and others that the theatres

presented an opportunity for thieves and whores as well, but of course he and

his faction loathed the theatre.

There were two kinds of acting companies operating, exemplified by

the two most important troupes working in London at that time.

The Lord Chamberlain’s men, the company of Shakespeare and the sons of James Burbage, Richard (the lead actor) and Cuthbert, was run on a sharing system. Five or six of the actors became shareholders in the business. In addition to the roles they played, they “shared” various management responsibilities. They also took “shares” of the profits, and became rather wealthy men. This core company hired other actors at set salaries, called “hirelings” who received decent wages but never shared profits. The company also made use of apprentices, young boys, who were trained by older actors to play, most usually, women’s roles. After Queen Elizabeth died in 1603, her successor King James I, took over the protection of this acting company, and it became known as the King’s Men.

The Lord Chamberlain’s men, the company of Shakespeare and the sons of James Burbage, Richard (the lead actor) and Cuthbert, was run on a sharing system. Five or six of the actors became shareholders in the business. In addition to the roles they played, they “shared” various management responsibilities. They also took “shares” of the profits, and became rather wealthy men. This core company hired other actors at set salaries, called “hirelings” who received decent wages but never shared profits. The company also made use of apprentices, young boys, who were trained by older actors to play, most usually, women’s roles. After Queen Elizabeth died in 1603, her successor King James I, took over the protection of this acting company, and it became known as the King’s Men.

The prime rival of the Lord Chamberlain’s men was the Lord

Admiral’s men, and that troupe was run differently. One man, Philip Henslowe,

produced the plays and pocketed the profits. He paid all his actors, and

one at least (Edward Alleyn, the company’s star and the original Faustus)

was paid very well.

The Stuart Court

Masque

Court masques were quite popular during the reign of Henry VIII, less so under Elizabeth. But in 1603, when James I, the first Stuart king, James I, came to the throne, masques were played frequently and in ever increasing splendor. Under James one masque per year was presented at court, and under his successor Charles I, two per year.

The idea of the masque was to dazzle, but also to show an

idealized vision of monarchy. The plots are allegories with the king at

the center, usually depicted as a mythological figure that brings order out of

disorder. Woven into the allegorical plot were grand masquing dances,

usually three of them, performed by groups of dancers of a single sex, except

in the case of even more elaborate “double masques,” which featured equally balanced

groups of men and women. Each dancer was accompanied by a torchbearer,

and in the masques the torchbearers occasionally performed a dance of their

own.

Masques were expensive. In 1618, James I spent 4,000

pounds on one masque alone. To put this in context, that amount was more than

all the money spent on all the plays by companies brought to court during his

entire reign! In 1634, a masque called The Triumph of Peace cost 21,000 pounds! Part of this money

went to the writer, and given all the money to be made, writers vied ardently

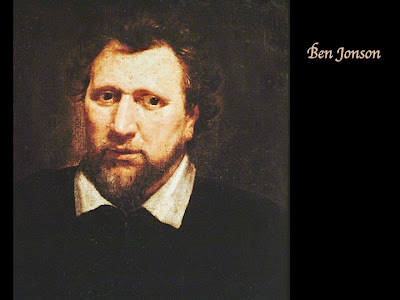

to compose court masques. The primary writer was Ben

Jonson, but he quit in a huff in 1631 after a dispute with Inigo Jones, the man who designed the Stuart court masques. Jonson left because at the center of the masque were music and spectacle, with just enough dialogue to hold the action together. The most important story elements were not spoken but danced, and danced by courtiers. It was considered proper, even elegant, for

courtiers to dance, and they spent a lot of time learning the

current favorites. The dialogue of the masque was spoken by professional

actors, because no proper courtier would stoop to ACT! Dance, yes, but to

insinuate that a courtier was anything like those scandalous professional actors!

It wasn’t done! The visual is paramount in the masque, offered in the

grand dances and in the lavish costumes and scenery provided by Jones and

others. No wonder Jonson, a major egotist, was miffed – his words were

being upstaged by scenery!

Jonson, but he quit in a huff in 1631 after a dispute with Inigo Jones, the man who designed the Stuart court masques. Jonson left because at the center of the masque were music and spectacle, with just enough dialogue to hold the action together. The most important story elements were not spoken but danced, and danced by courtiers. It was considered proper, even elegant, for

Many of the masques were performed in the banqueting hall of

Whitehall Palace. Inigo Jones designed the building himself, as well as

the masques that were played there. In his designs, Jones

introduced the Italian scenic methods into England. He’d studied extensively in Italy where he learned to use temporary proscenium arches, with angled wings, periaktoi, and eventually flat wings nested and placed in grooves to dazzle the audience with scene shifts. Jones learned all this from Giulio Parigi (whom I hope you’ll remember from the Italian Renaissance), and in fact copied many of the Italian’s designs for the English masques. Jones also provided machines (like Sabbattini’s in Renaissance Italy) that flew mythological figures in on cloud machines.

introduced the Italian scenic methods into England. He’d studied extensively in Italy where he learned to use temporary proscenium arches, with angled wings, periaktoi, and eventually flat wings nested and placed in grooves to dazzle the audience with scene shifts. Jones learned all this from Giulio Parigi (whom I hope you’ll remember from the Italian Renaissance), and in fact copied many of the Italian’s designs for the English masques. Jones also provided machines (like Sabbattini’s in Renaissance Italy) that flew mythological figures in on cloud machines.

The culmination of Jones’s scenic efforts was the masque Salmacida Spolia, designed in 1640, with

a text by William Davenant (a rising young writer who would become one of the

most important men in English theatre when the king was restored in 1660). This masque marks the first time we can document the wing and groove system in England, but remember for reference that the more sophisticated chariot and pole system was already being used in Italy and France. It was Jones’s wing and groove system that would prove the victor over the old style mansion and platea staging of the outdoor public theatres, when the theatres re-opened in the Restoration.

most important men in English theatre when the king was restored in 1660). This masque marks the first time we can document the wing and groove system in England, but remember for reference that the more sophisticated chariot and pole system was already being used in Italy and France. It was Jones’s wing and groove system that would prove the victor over the old style mansion and platea staging of the outdoor public theatres, when the theatres re-opened in the Restoration.

To give an idea of what a masque might entail, here’s a brief

description of the major action in Salmacida

Spolia:

Discord, a malicious fury, appears in a storm, and by the

invocation of malignant spirits endeavors to disturb England; but the malignant

spirits are surprised by a secret power, Wisdom (in the person of the king and

attended by his nobles; then the queen and her ladies are sent down (via

machine) from heaven and reward Wisdom because he reduced the storm that threatened

into a wonderful (and scenically splendiferous!) calm.

Ironically, just two years after this lavish production, the

Puritans dispersed the king’s “calm,” threw him out of office, and then

executed him in 1649. He was beheaded, ironically enough on a scaffold set up at the banqueting house. During the nasty civil war during this time, Puritand and parliament destroyed most of the theatres as well. But the king’s son was safe abroad and in 1660 would be restored to the throne as Charles II. But more of that later!

executed him in 1649. He was beheaded, ironically enough on a scaffold set up at the banqueting house. During the nasty civil war during this time, Puritand and parliament destroyed most of the theatres as well. But the king’s son was safe abroad and in 1660 would be restored to the throne as Charles II. But more of that later!