|

| One of the most specatular settings for a Roman theatre is in Taormina in Sicily |

The building had three stories, supported on 360 columns...The

lower level was marble; the second, glass -- a sort of luxury which since then

has been quite unheard of; and the upper most was made of gilded wood.

The lowermost columns... were 38 feet high, and placed between them...were

3,000 statues. The theatre could accommodate 80,000 spectators. (Nagler, A Sourcebook in Theatre History)

Unless Pliny was dreaming when he wrote this, even if he

exaggerated immensely this temporary structure would have been impressive. The

Romans were engineers, remember, and not just from this description but from

the many structures still standing after about 2,000 years, they were damned

fine ones. Shortly after the extravagance of Scaurus, another politician named

Gaius Scribonius Curio strove to compete with the earlier effort, and had two

large wooden temporary theaters built close together; each nicely poised,

turning on a pivot.

Before noon a spectacle...was performed in each, with the

theatres back to back...Then suddenly, during the latter part of the day, the

two theaters would swing around to face each other with their corners

interlocking and, with their outer frames removed, they would form an

amphitheater in which gladiatorial combats were presented. When the pivots

were overworked and tired, another turn was given to this magnificent display,

for on the final day, the theatres, still in the form of an amphitheater, were

cut through the center for an athletic spectacle, and finally, their stages

were suddenly withdrawn on either side to exhibit on the same day combat

between those gladiators who had previously been victorious.

(Pliny the Elder, quoted in Nagler, A Sourcebook in Theatre History)

Hard to imagine, right? And very likely exaggerated...still...

The first

permanent theatre in Rome was the Theatre

of Pompey, built in 55 BC. Why so late? Well, a significant faction in

Republican Rome were concerned about the corrupting influence of theatre.

In fact theatres had been planned and banned several times during the republic,

notably a performance space in 154 BC on which construction had begun when

officials ordered its destruction on the grounds that theatre could be

injurious to public morals. Not the last time in history that a phrase such as

that would be used against the theatre!

The Roman senate

decreed that no one could build seats for a theatre... ”nor should anyone sit

down at any dramatic performance in the city [of Rome] or within a mile of the

gates,” on the assumption that if they could keep people uncomfortable, they

could minimize theatrical activity.

However, if we

can believe ancient Roman writer Tertullian, Pompey (Julius Caesar’s one-time

colleague, later his enemy) managed to get away with building stadium seating

by constructing a small temple to Venus at the highest point at the rear of the

auditorium. He could argue -- and did -- that these weren’t seats in a

theatre, but steps to the temple of Venus. If this was the case, I dub

Pompey the cleverest Roman of them all!

Let’s now set up

a prototypical Roman theatre. We have lots of help here because of a

brilliant architect/city planner named Vitruvius,

who wrote a multi-volume treatise called De Architectura. One volume

dealt with theatre, and in it we learn that Roman theatres were based on Greek

models (and were sometimes built over Greek shells).

BUT! Although there

are many similarities between Greek and Roman theatre spaces, there are also

major differences. One is in the basic structure of the

building. You’ll remember that the Greeks relied on natural hillsides

for the theatron, the fan-shaped

auditorium. The orkestra was a circle

on the ground at the bottom of a hill (and in later Hellenistic theatres ¾ of a

circle), separate in a sense from the theatron.

The skene too was next to the orkestra circle, but was also a separate

unit. Because the Romans exploited the tremendous architectural

possibilities of concrete (which they invented) and the arch, by building one

series of arches atop another, strengthened by concrete, they were able to

erect a single freestanding building which incorporated all the separate

elements of the Greek theatres into one unit.

The auditorium

was called the cavea, divided by

several vertical and at least one horizontal aisle. The audience entered

from the

bottom, climbed steps in the interior of the structure and entered (or were “spit out” into) the seating area through openings called vomitoria, which meant literally “up from under.” We have retained these doors in arena and thrust stages today, and the name is usually shortened to “vom.” And yes, we are aware of other meanings for this word, often encountered by many of my students late on a Friday night...there are even stories that the term came from the audience members who became a bit queasy when a lion was tearing apart a Christian martyr, running out these doors so they could, well, do the “up from under” thing.

bottom, climbed steps in the interior of the structure and entered (or were “spit out” into) the seating area through openings called vomitoria, which meant literally “up from under.” We have retained these doors in arena and thrust stages today, and the name is usually shortened to “vom.” And yes, we are aware of other meanings for this word, often encountered by many of my students late on a Friday night...there are even stories that the term came from the audience members who became a bit queasy when a lion was tearing apart a Christian martyr, running out these doors so they could, well, do the “up from under” thing.

The stage house

was called the scaena, a mere

Latinization of the Greek skena.

The front wall of the scaena was

called the scaena frons -- it was

huge, and elaborately decorated with columns,

niches, porticoes and

statues. The stage, called the pulpitum,

jutted out from the scaena, about 5

feet off the ground, between 20 and 40 feet deep, and anywhere from 100 to 300

feet long. On the scaena frons

from 3 to 5 doors opened onto this pulpitum.

The orchestra, which in fifth century BC Greece had been the center of the

action, was cut into a half circle, and was used primarily to seat a few

privileged audience members, though there were theatrical uses for it in some

entertainments.

|

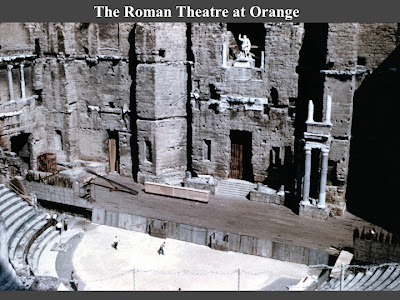

| This theatre, in the south of France, is one of the very best preserved anywhere |

Let’s look more

closely at the stage. Many questions have been asked about the scaenae frons. We know there was depth,

we know

the niches were good for eavesdropping scenes, of which there were many

in Roman comedies, and we know that there were usable doors for comedy which

represented different houses (usually 3) involved in the play. In some

theatres there were doors at each side of the stage, one leading to the center

of town (the forum?), the other leading out of town. The ornate scaenae frons provided most of the

scenic background, but it’s been argued that periaktoi might have stood on either side of the stage or in the

niches, and that these three-sided objects could be turned when necessary to

change a scene. Others have argued persuasively for pinakes placed within the openings of the scaenae frons, with paintings which could have been relatively

realistic, or at least painted in perspective (per Vitruvius). There is

evidence in wall paintings found in villas in and around Pompeii that MIGHT

depict scenes from the Roman stage, but even this visual evidence is

questionable.

|

| A photo I took when I visited Orange in 1999 A stage is being prepared for the summer opera season performed here annually. The few workers you see will give you a sense of scale. |

Finally, the

Romans used two kinds of curtains in their theatricals. One was called

the auleum -- it was a front curtain,

which was dropped into and lifted from a slit in the downstage edge of the pulpitum. In this way a scene

could be suddenly revealed, though there is not much call for that in the

existing comedies from the period. The other curtain was called the siparium. A rear curtain hung on the scaenae frons, this was apparently used

primarily in mime performances as a scenic background. Related to curtains but

pertaining to the audience was the velarium,

made of velum, which was used in sail-making as well, a retractable

curtain/ awning on some theatres and amphitheatres, most notably the Colosseum,

which acted as a screen from the sun for at least some of the many costumers

that attended events in those places.

Roman actors were

males (except in mime, where, as in Greece, women performed along with men),

proficient in singing and dancing as well as in speaking, and most of them specialized

in either comedy or tragedy. One of the most famous Roman actors

was apparently proficient at both forms, though he preferred comedy. His name was Roscius, and he must have been the Laurence Olivier of his day -- he was certainly the most famous name that comes down to us from ancient Rome -- Polonius mentions him in Hamlet when the actors are on the way in: “when Roscius was an actor in Rome...” In the nineteenth century it was common to label a particularly good actor as a “Roscius,” especially when he or she had a specialty: a child star (and there were several) was known as “the infant Roscius;” and Ira Aldridge, a black actor, was billed as “The African Roscius.” The Roman Roscius was so well regarded that he was raised to the nobility. Most actors weren’t so lucky – most were slaves.

was apparently proficient at both forms, though he preferred comedy. His name was Roscius, and he must have been the Laurence Olivier of his day -- he was certainly the most famous name that comes down to us from ancient Rome -- Polonius mentions him in Hamlet when the actors are on the way in: “when Roscius was an actor in Rome...” In the nineteenth century it was common to label a particularly good actor as a “Roscius,” especially when he or she had a specialty: a child star (and there were several) was known as “the infant Roscius;” and Ira Aldridge, a black actor, was billed as “The African Roscius.” The Roman Roscius was so well regarded that he was raised to the nobility. Most actors weren’t so lucky – most were slaves.

The actors wore

masks, complete headdresses with wig and beard

attached. Costumes consisted of the tunic (a fitted linen garment worn next to the skin and a toga, a heavier wool cloak draped over the tunic. But there were many variations dependent on genre of drama being played, and the social position of the character. Color was important. Royalty, for example, was indicated by purple borders on the costume (toga praetexta).

attached. Costumes consisted of the tunic (a fitted linen garment worn next to the skin and a toga, a heavier wool cloak draped over the tunic. But there were many variations dependent on genre of drama being played, and the social position of the character. Color was important. Royalty, for example, was indicated by purple borders on the costume (toga praetexta).

Music was more

extensive in Rome than in Greece – again the flute was the principal instrument.

The Roman flute consisted of two 20-inch pipes, bound to the musician’s head so

that both hands could work the stops. Stringed instruments and percussion were

also made use of in the theatre.

How about the

stage hands? We don’t find much in history, though I can’t imagine there

weren’t a lot of them, and along with hordes of slave labor, a happy few had to

be highly skilled. One of the few pieces of evidence that comes down to us

is the sad story of the technicians who had apparently botched a show at the

Colosseum. For their screw-up the Emperor Claudius had them

executed...think about that the next time you miss a cue!

The decline of

the Roman theatre, and Rome itself paralleled the growth of the Christian

(Catholic) Church. That from the dead bodies of Christians eaten by lions

and clobbered by gladiators

should arise an institution as powerful and lasting

as the Roman Catholic Church is at least surprising -- but the fact is that in

313 AD Emperor Constantine, in the Edict of Milan, gave freedom and official

standing to the Church; and by 393 AD Theodosius I outlawed any other

religion. So in the days of the late empire, the dominant religion was

Christianity -- and Christians did not like the theatre and attacked it,

ostensibly because it was related to pagan rituals, but also because some

theatrical activity, most often in Roman mime troupes, made fun of Christian

ceremonies. This was enough for the Church to brand actors (and theatre)

as immoral and worse. Again, this is hardly the last time in this course

that we’ll hear that refrain. I should say that theatre had gotten

increasingly decadent by the late empire (nudity and flagrant sexual acts were

usual on the late empire stage). So there were a few good reasons that the

Church found theatre repulsive.

|

| The patron saint of actors was martyred in the Colosseum |

Of the near

constant attacks on the theatre by the Church, perhaps

the most important was a

decree by the Council of Carthage in 398 AD that any person who even attended

theatre on holy days of the church would be excommunicated. This

basically meant that the sinner who attended would not pass go (to heaven);

instead…would go directly to hell. It was even worse for actors, who were

forbidden the sacraments under this decree, which meant automatic

excommunication, and while the audience was let off hook relatively early on,

the portion of the decree pertaining to actors was not rescinded until the late

eighteenth century. After the fall of the Roman Empire it was used selectively,

but it could be quite a punishment to the actor who was accused, and a stern lesson

to others. The best example is Molière, who was refused Christian burial

on the grounds of this ancient church council edict.

So, the Christian

Church was one of the prime reasons for the fall of Roman theatre, as well as

for weakening the empire itself. But there were other causes. The

so-called “barbarians” were pushing towards Rome and eating away at its

empire. As early as 330 AD

the emperor Constantine thought it wise to divide the empire and move the capital from Rome east to Byzantium. He built a city he called Constantinople, and it’s now called Istanbul. But, although the Byzantine empire was very important for a number of reasons, it wasn’t particularly significant in its theatre, probably because of its Christian base. What records come down to us indicate popular entertainments similar to those in Rome, but theatre was looked down on by the Christian elite.

the emperor Constantine thought it wise to divide the empire and move the capital from Rome east to Byzantium. He built a city he called Constantinople, and it’s now called Istanbul. But, although the Byzantine empire was very important for a number of reasons, it wasn’t particularly significant in its theatre, probably because of its Christian base. What records come down to us indicate popular entertainments similar to those in Rome, but theatre was looked down on by the Christian elite.

For our purposes,

Byzantium is MOST important for the period just before it fell to the Turks in

1453. The libraries of Constantinople were famous for their collections

of ancient Greek and Roman texts. As it became apparent that the end was coming,

scholars fled west back to Italy with as many manuscripts as they could carry –

many of the remaining Greek and Roman plays were preserved at this time.

|

| figurines of Roman mime actors - comic or grotesque? |

No comments:

Post a Comment