In the area of production, Spanish theatre was very similar to that of Elizabethan England. The public theatres were called corrales, and were somewhat like their English counterparts. As with London in England, we know more about Madrid than any of the other Spanish cities, so we’ll focus on it. Public theatres begin to appear in Madrid during the mid-1500s, run by those guilds known as cofradias. In 1568 the first cofradia began renting out space in a courtyard called the Calle de Sol to produce theatre. Professional troupes played, but this cofradia and others collected a portion of the gate for its charitable work. In fact, until 1615 three of these organizations controlled all the theatre in Madrid.

|

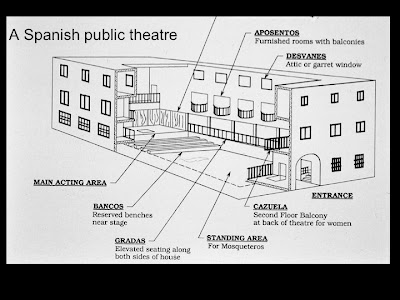

| This drawing is not terribly accurate, but it gives some idea of the set-up. |

The two most important corrales in Madrid were the Corral de la Cruz, begun in 1579, and the Corral del Principe in 1585. From then until the mid-eighteenth century, these two theatres were the primary public theatrical spaces in Madrid.

The two were similar, from what we can tell. They were

modeled on courtyards. The ground level of these corrales was a patio, or

pit, which faced a stage. Closest to the stage there were a few

rows of benches, called taburetes. Behind the taburetes stood those who’d bought the cheapest tickets. Often they were the rowdy mosqueteros, (musketeers) who were looking to be seen and also frequently looking for trouble. At the rear of this patio there was a refreshment stand (alojero). Rising from the patio on the left and right were the gradas, stadium style seating; above the gradas were balcony-like openings in the buildings which supported the sides

of the

theatre. More expensive seats were to be had here, called aposentos. Above the aposentos there was a crammed upper

gallery called the desvanes.

Opposite the stage on the level above the refreshment stand was a cazuela (one scholar has translated it

as “stew-pot”), a gallery where unaccompanied women were required to sit.

Above the cazuela were two levels of

boxes (tertullia) for city officials

and their guests, also for the clergy.

rows of benches, called taburetes. Behind the taburetes stood those who’d bought the cheapest tickets. Often they were the rowdy mosqueteros, (musketeers) who were looking to be seen and also frequently looking for trouble. At the rear of this patio there was a refreshment stand (alojero). Rising from the patio on the left and right were the gradas, stadium style seating; above the gradas were balcony-like openings in the buildings which supported the sides

|

| This theatre, about an hour and a half south of Madrid,still exists and offers performances. |

The stage itself was a bare platform, much like the Elizabethan

stage except that it did not thrust into the yard. Instead stage boxes

flanked each side of the Spanish stage. The stage was backed by a

two to

three level facade which was somewhat ornamental, and which was pierced by two

doors on either side of a larger discovery space. The stage at the Corral

del Principe measured about 28 feet wide by 14 1/2 feet deep. The

second level was used for discoveries and window scenes, but often represented

towers, hills, and so forth. Staging was also very like that on the

public stages of England. There were set pieces similar to those on

Henslowe’s list, and although some painted pieces on the facade represented

specific locations, there was no attempt at Italian style perspective

vistas.

|

| The theatre at Almagro is much smaller than the theatres in Madrid, but you can get a pretty good look at the stage from this shot |

Costumes were generally also similar to those in Elizabethan

England, except that since we have more records available on costumes from

Spain, we learn that some actors were drawn to extravagant dress. In fact

there was a royal decree in 1653 forbidding actresses to wear strange

headdresses, wide-hooped skirts, skirts that did not reach the floor, and worst

of all, dresses with low-cut necklines! Otherwise, costumes were

contemporary dress with exceptions for classical drapings and for specialty

roles that were identified with a particular kind of apparel.

Some actors were members of troupes run by shareholders, though in a different sense than in England as they

shared in the company, but never owned theatres. There were also some instances of a single

manager in control, like Henslowe in England, who hired all his actors on an

individual basis. A major difference between Spain and England is that

after 1587 women were allowed to perform on the Spanish stage. The Church

didn’t approve of women on stage,

but the alternative was even more upsetting. The idea of cross-dressing by

either sex was thought to be morally ambiguous – at least – by the Church

fathers. So a compromise was reached: women were allowed to perform, but

as of 1599, after years of dispute between church and secular authorities, they

had to be married to or daughters of men in the company. The Church made it

difficult for women in particular and actors in general, attempting to uphold

the ancient Roman law that actors were to be forbidden the sacraments. In

practice however they used this law only in exceptional circumstances.

Nevertheless, these edicts remained on the books in Spain until the twentieth

century.

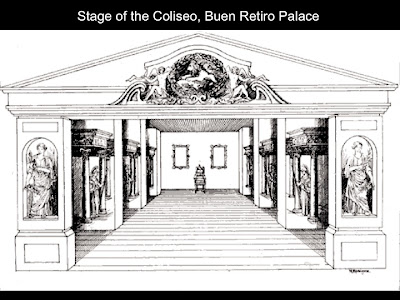

In addition to public theatre there were extensive and often

lavish entertainments at court. The earliest examples were dances similar

to Stuart court masques that featured courtiers. Later,

however,

professional acting companies were employed. In the court theatres Italian scenic style was imported and exploited.

The prime designer was a Florentine, Cosme

Lotti, who began to work his scenic wonders in 1626 at both the Alcazar

palace and at the Buen Retiro palace in Madrid. Perhaps his best-known

entertainment was The Greatest

Enchantment is Love (1635), which was written by Calderon. The story

is about Ulysses and Circe, and to set it properly, Lotti built a floating stage

on a lake, lit it with 3,000 lanterns, and featured incredible effects

including a shipwreck, a chariot drawn through the water by dolphins, and the

destruction of Circe’s palace. The king and court watched the spectacle

from gondolas.

|

| One of the court theatres in Madrid - this should look familiar, as it apes the Italian Renaissance stage |

|

| The artificial lake at Buen Retiro Palace, where The Greatest Enchantment is Lovewould likely have been performed |

There was one more area in which Spanish theatre flourished.

As early as 1567 there are records of Spanish theatre being performed in the

new world. In that year, at a Spanish mission near Miami Florida, Spanish

settlers and soldiers enacted a religious play to teach the Native Americans

they encountered about the Catholic Church, in what you might call a

comparatively subtle and gentle effort to convert them to the Church.

Before the end of the sixteenth century Spanish colonists around El Paso Texas

were

engaged in similar activity. A secular theatre flourished as well in the areas of the new world conquered by Spain, and one of its writers was female. Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz (1648?-1695) wrote for the theatre in Mexico City, where she lived in a convent. This well-educated nun, one of the earliest identifiable female playwrights, wrote religious plays as well as a few secular pieces, including The Trials of a Noble House (1683) and The Second Celestina (1675), which she co-authored with Augustin Salazar y Torres. So the first western theatre in the area that would become the United States was Spanish, produced throughout its golden age.

engaged in similar activity. A secular theatre flourished as well in the areas of the new world conquered by Spain, and one of its writers was female. Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz (1648?-1695) wrote for the theatre in Mexico City, where she lived in a convent. This well-educated nun, one of the earliest identifiable female playwrights, wrote religious plays as well as a few secular pieces, including The Trials of a Noble House (1683) and The Second Celestina (1675), which she co-authored with Augustin Salazar y Torres. So the first western theatre in the area that would become the United States was Spanish, produced throughout its golden age.

By the late seventeenth century, however, the Spanish empire was in a major downhill slide, and the theatre, mirroring the empire, entered a decline it didn’t pull itself out of until the early twentieth century, which is when we’ll next address it.

Up next? French Neoclassical Theatre!

No comments:

Post a Comment