|

| Cooperation between the arts: Edvard Munch design for Ibsen's Ghosts |

Then, in the early years of the twentieth century, the relatively small

rebellions that peppered the nineteenth century turned into revolution. The

most vivid illustration was the Great War, later known as World War

I. Historian Barbara Tuchman, writing about this “war to end all

wars,” described sparkling, red-clad cavalry troops as excellent targets for

the dull black guns that methodically blew the horsemen off the face of the

earth.” (Guns of August,

New York: Ballantine Books reprint 1994)

In a more recent account of the First World War, author John Keegan

asserted that it was an unnecessary and tragic conflict (The First World War, New York: Vintage

Books, 2000); unnecessary in that the chain of events that led to its

outbreak could have been stopped before it began; tragic in that it destroyed

10 million human beings. Keegan points

out that when the Second World War came in 1939, it was far worse than World

War I, but it was unquestionably the outcome of the first, and when it finally

broke out the knowledge that it would come was appallingly clear. In 1914, however, the war came as an enormous

shock to Europeans, many of whom had never dreamt such a nightmare could occur.

The new order that developed from late nineteenth century

continuing into the beginning of World War I, is labeled “modern,” a difficult

word to define. Earlier dominant trends in the arts, Neoclassicism,

Sentimentalism, Romanticism, Realism, are relatively clear and useful

terms. The “modern” is so vague a concept, proceeding from as well as

breaking away from traditions often at odds with each other, that it may be

better to describe the particular people and their work that were categorized

as modern, than to attempt a specific definition.

To begin, let’s look at slides of two paintings and allow pictures

to say a thousand words. The first (Renoir, “The Bathers,” painted in the

impressionist style during the 1890s) was a very trendy way to look at women

(the garden, the world) in the very late nineteenth century. The second

(Picasso, “The Demoiselles d’Avignon,” 1907) is how one painter at least began

to see women, and the world, less than 20 years later! Obviously,

something major had begun to happen; something radical, fundamental, was changing

throughout the west.

Theatre, as well as other art, reflects the radical shift in

culture, and in the next weeks we’re going to uncover sea changes in the

theatrical form. In order to show you this transformation, I’ll be

handing you pieces of a patchwork quilt that you’ll have to stitch together.

Probably the best – really the ONLY – place to begin is in Norway,

where a writer who bears the onerous title “the father of modern drama” was

born. Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906)

towers above all other dramatic authors of his age.

Michael Meyer, Ibsen’s definitive English biographer, has explained how unusual, surprising, almost unheard of was the rise of this author. After all, he was Norwegian. Throughout cultured Europe no one knew the language, no one knew many if any Norwegian writers before Ibsen, and yet he was named “the father!” It was as if, Meyer suggests, theatre today would be revolutionized by an Eskimo!

Michael Meyer, Ibsen’s definitive English biographer, has explained how unusual, surprising, almost unheard of was the rise of this author. After all, he was Norwegian. Throughout cultured Europe no one knew the language, no one knew many if any Norwegian writers before Ibsen, and yet he was named “the father!” It was as if, Meyer suggests, theatre today would be revolutionized by an Eskimo!

Ibsen passed through three major phases in his writing. His

first great plays were romantic verse dramas, whose tortured heroes were the

title characters of the plays: Peer

Gynt (1867) and Brand (1866). In

the first, a man avoids issues by skirting them; in the second, a man is so

sure of his own vision that he sacrifices everything to it.

Ibsen soon moved towards the realistic style, reading and making

use of the Frenchman Scribe’s well-made play formula, but placing great

importance on character as well as on plot, and focusing on new themes, no

matter how

shocking, even revolting the subject matter. A Doll’s House (1879) is a fine example. Similar to a play by Scribe or Sardou, it could have been called The Unopened Letter, given all the suspense Ibsen created when Nora tries to keep Torvald from reading his mail. But Ibsen was going for more than just a well-made suspense drama. The characters are highly developed. There are no cardboard good and bad guys; and whereas Scribe would have built at least as much suspense but wrapped up the story happily, Ibsen had Nora do the unthinkable; walk out the door. And the slam was heard round the world.

shocking, even revolting the subject matter. A Doll’s House (1879) is a fine example. Similar to a play by Scribe or Sardou, it could have been called The Unopened Letter, given all the suspense Ibsen created when Nora tries to keep Torvald from reading his mail. But Ibsen was going for more than just a well-made suspense drama. The characters are highly developed. There are no cardboard good and bad guys; and whereas Scribe would have built at least as much suspense but wrapped up the story happily, Ibsen had Nora do the unthinkable; walk out the door. And the slam was heard round the world.

A Doll’s House made Ibsen famous internationally, and he went further into the new realism he created with Ghosts (1881), probably the most influential work of Ibsen’s realistic

period. In it, Mrs. Alving has been trying to protect her artist son from the truth about his dead father, who had seemed a pillar of society, but who secretly had affairs with whomever he could, including the family’s own maid. By the maid Alving had a daughter, now an attractive young woman serving Mrs Alving…as a maid! In the first act of the play, Mrs Alving’s son Oswald, just returned from a Bohemian life in Paris, begins to flirt with the maid, and as they laugh and kiss (step-brother and sister!) at the end of the act, Mrs Alving stares at the audience and whispers the word: “Ghosts!” in one of the great act endings in modern theatre.

To make matters even worse, Mr. Alving is long dead, but had

contracted syphilis and passed it on genetically to his son. As the

secrets come out in Ibsen’s intricate plot, Oswald is beginning to go mad from

the effects of the sins of his father – “the sins of the father are visited

upon the son” – and at one point he begs his mother to administer the drug

which will kill him as he succumbs to the disease. The final curtain

falls with Oswald, now victim to syphilis, incoherently babbling “The

sun! The sun!” and his mother holding the drug, unable to decide if she

can indeed administer it!

The shocking subject matter of Ghosts

– one didn’t dare breathe the word “syphilis” in polite society, much less

write a play about it – attracted the new, small theatres springing up

throughout Europe as much as it repulsed the mainstream public and

press. Some comments from journalists of the day about Ghosts:

“one of the filthiest

things ever written in Scandinavia!”

“an open drain”

“a loathsome sore

unbandaged”

“a dirty act done

publicly”

Whatever they thought, with plays like Ghosts and A Doll’s House,

Ibsen made the theatre, after 100 years of melodrama and burletta, an accepted

medium for the most serious and profound writing.

Ibsen’s later writing did not lose the social awareness of his

realistic phase, but his late plays moved strongly towards

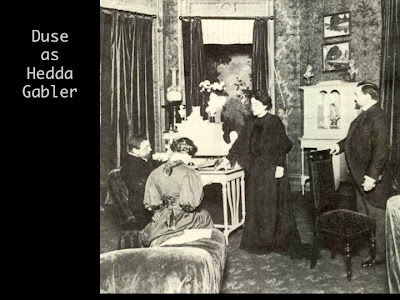

symbolism. Indeed, in Ibsen’s work there was always a strong use of symbols. As early as A Doll’s House, the very title is a symbol, and 1884, in The Wild Duck, the symbol takes on more power still. In Hedda Gabler, the situation remains relatively realistic, but Ibsen manipulates the language so that nearly every conversation exists on both realistic and symbolic levels, especially the conversations between Lovborg and Hedda, and Hedda and Brack. When Hedda (speaking to herself at this point) is burning Lovborg’s manuscript, she’s symbolically burning his and Thea’s “child!”

symbolism. Indeed, in Ibsen’s work there was always a strong use of symbols. As early as A Doll’s House, the very title is a symbol, and 1884, in The Wild Duck, the symbol takes on more power still. In Hedda Gabler, the situation remains relatively realistic, but Ibsen manipulates the language so that nearly every conversation exists on both realistic and symbolic levels, especially the conversations between Lovborg and Hedda, and Hedda and Brack. When Hedda (speaking to herself at this point) is burning Lovborg’s manuscript, she’s symbolically burning his and Thea’s “child!”

|

| Elizabeth Marvel in the New York Theatre Workshop production |

Ibsen wrote most of his plays in self-imposed exile from Norway. For 27 years (with infrequent and brief returns home) he lived in European cities, among them Rome, Dresden and Munich. When he returned (in his 60s) to Norway, his plays began to take on a more mystical, religious, poetic nature. Probably the greatest play of this period is The Master Builder (1892). Solness is an architect in late middle

|

| Terrific tv production of The Master Builder 1988 Miranda Richardson as Hilda, Leo McKern as Solness |

high up the spire of a church he had just completed, and hang a wreath atop it. He remembers too, and says, “Yes, and when I looked down someone was wildly waving a kerchief -- it made me dizzy and I nearly fell!” Hilda says, “That someone was me!” She goes on to remind him that afterwards he’d been invited to her parents house, and that when there, he and she spent some time alone together. She claims he sat her on his knee, kissed her hard, on the lips -- Solness,

|

| Hilda with Solness's long-suffering wife, played brilliantly by Jane Lapotaire |

|

| Hilda wildly waving the kerchief - Miranda Richardson was as frightening as she was beautiful in this role |

Robert Brustein (in his excellent study of modern drama, The Theatre of Revolt, 1964) called The Master Builder “A great cathedral of a play, with dark mystical strains which boom like the chords of an organ.” Symbols dominate the action in this and Ibsen’s other late plays. Ibsen predates and is a major influence on the symbolist movement. We’ll speak of this movement later, but symbolism tends to give ordinary objects significance far beyond their literal meaning, and thus enlarges the scope of the dramatic action.

Ibsen’s writing breaks down into three phases, but is perhaps

better viewed as variations on the same theme: rebellious heroes struggling for

integrity, and the great conflict of duty to oneself versus duty to

others. Ibsen said, “To write is to sit in judgment on oneself.” He

stated: “Before I write one word, I must know the character through and

through; I must penetrate to the last wrinkle of his soul -- then I do not let

him go until his fate is fulfilled.” But though he wrote some of the great

realistic drama, and dealt with what many people saw as sordid, forbidden

subjects, he compared his writing to the naturalistic movement, of which he did

not approve: “Zola,” he said, goes to bathe in the sewer. I go to cleanse

it.”

Ibsen is indeed the father of modern drama, but he had three close

relatives, so to speak, in Chekhov, Shaw, and

Strindberg. These four are generally agreed to be the greatest writers at the beginnings of modern drama, and their plays continue to be produced today. We’ll look at all of these important writers in some detail before we look at other aspects of the modern theatre, but first let’s travel the shortest distance from Ibsen’s Norway -- to Sweden -- and examine the interesting case of August Strindberg.

Strindberg. These four are generally agreed to be the greatest writers at the beginnings of modern drama, and their plays continue to be produced today. We’ll look at all of these important writers in some detail before we look at other aspects of the modern theatre, but first let’s travel the shortest distance from Ibsen’s Norway -- to Sweden -- and examine the interesting case of August Strindberg.

“Strindberg, says Robert Brustein, “writes

himself, and the self he continually exposes is that of alienated modern man,

crawl-ing between heaven and earth, desperately trying to pluck some absolute

from a forsaken universe.”

Like Ibsen, Strindberg began writing romantic sagas, but his first

great writings are in the realistic mode, the most important The Father (1887) and Miss Julie (1888). The Father tells of the struggle between

a husband and wife. He’s a strong confident captain at the beginning of

the play, sure of himself until he is given to believe that he is not the

father of his daughter. Is it all in his mind? Is his wife

deliberately taunting him with the possibility? Is it true? Whatever the

truth, his confidence deteriorates, and he descends into madness. After

he has nearly shot his daughter and turns the gun on himself, only to find that

it has been unloaded, his old nanny gently tricks him into putting on a

straight jacket, and the father lies on the floor trying hopelessly to yank

himself free, as his wife stands over him -- now SHE has the power.

Although The Father is

set in a drawing room, the play’s setting, says Robert Brustein, “is less a

bourgeois household than an African jungle, where two wild animals, eyeing each

other’s jugular, mercilessly claw at each other until one of them falls.”

More than any dramatist before him, Strindberg bares his soul on stage, and the

chief burden of his soul is the struggle between man and woman.

This struggle, demonstrated in The

Father, is further explored in Miss

Julie. In this play, a servant, Jean, seduces his mistress Julie (or

does she seduce him?) during Midsummer Eve festivities. Then, when he

begins to fear that their impossible union will be found out, he induces her

to, or at least doesn’t stop her from, cutting her throat. The dramatic

design of Miss Julie is like two

intersecting lines moving in opposite directions: Jean reaches up, Julie

falls down. Strindberg wrote this powerful play in a mere two weeks!

There is a strong basis for this theme of the struggle between man

and woman in Strindberg’s own life. Remember, Strindberg writes himself.

Strindberg adored his mother with a passion he described as “an incest of the

soul,” but he hated her as well. This love-hate relationship was

reflected in his relationships with his three wives. Strindberg wooed his first

while she was married to another. He worshipped her, helped her to get a

stage career, overwhelmed her, in fact. After which she divorced her husband

and married Strindberg. As soon as they were married he began to accuse her of

competitiveness, lesbianism, drunkenness, infidelity, uncleanliness, doubting

his sanity -- and not keeping the accounts!

He divorced his first wife, quickly married Frida Uhl, and the

same pattern repeated itself. Two years later he was separated

again. His last marriage was to Harriet Bosse, an actress 30 years

younger than he. In an angry letter to this wife, Strindberg wrote: “The

day after we wed, you decided that I was not a man. A week later you were

eager to let the world know that you were not yet the wife of August

Strindberg, and that your sisters considered you ‘unmarried’ ...we did have a

child together, didn’t we?”

In the Road to Damascus,

Strindberg poetically summed up his relationships with women, rather

poetically, but offers insight into what he at least saw as the basic struggle

between the sexes:

In woman I sought an angel, who could

lend me wings, and I fell into the arms of an earth-spirit, who suffocated me

under mattresses stuffed with feathers of wings! I sought an Ariel and I

found a Caliban; when I wanted to rise she dragged me down; and continually

reminded me of the fall...

In the mid 1890s, after his second divorce, Strindberg fell into a mental crisis, living for a time like a derelict in Paris. During this time Strindberg kept a diary, later published as

for the most part they were vastly different from his earlier, naturalist work. Strindberg had undergone a sea change, and this change was reflected in his work. He called the new plays “dream plays” in which reality was re-shaped, time and place was frequently illogically shifted, and the real and imaginary were merged. He wrote of alienated people lost in an incomprehensible universe. The best known of these are The Dream Play (1902) and The Ghost Sonata (1907), plays that predated the expressionist movement in drama, and strongly influenced that form and much other twentieth century theatre.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteMarvellously written piece, thank you so much for sharing. It got me all excited about C20 theatre again... I saw several of the productions you mention. I'm a big Ibsen admirer.

ReplyDeleteVery good article. I would just point out that the horror of Oswald and Regina flirting and kissing is that they are half-brother and sister, not stepbrother and sister. In other words, they are blood relations!

ReplyDelete