|

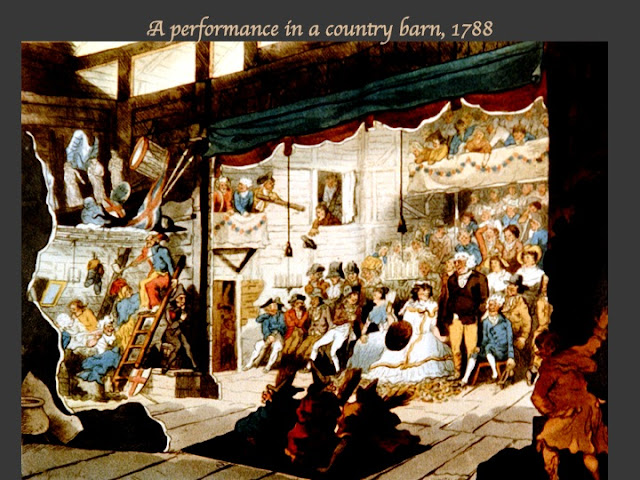

| One of the oldest theatres is this one in the north of England. It gives an idea of what London theatres looked like at the beginning of the eighteenth century - tiny! |

The second very important theatre in this century was the Covent Garden, which began its life in 1732. This theatre too was enlarged throughout the century. In its original incarnation it seated 1300; by 1793 it had been renovated to hold 3,000 audience members.

A third important space was the King’s Theatre, which featured opera primarily until 1789, when it was destroyed by fire. It was rebuilt and continued primarily as the home of opera and ballet well into the nineteenth century, after which its focus was on theatre. In 1914, for example, Shaw’s Pygmalion premiered here. But I find myself far ahead of my story!

Interesting sidebar (to Dr Jack at least, and not to keep

reminding you but this is theatre history according to whom? Enough said.)

this theatre began its life as the Queen’s Theatre in 1705, named in honor of Queen Anne, who was the monarch at the time. But Handel wrote most of his operas during the reigns of George I and II, so the theatre’s name changed to The King’s. To continue what seems interesting to me and may or may not be to you, in 1837, when Victoria became queen, it was re-named again, but not the Queen’s

Theatre – instead it was puffed up a tad, and called Her Majesty’s Theatre. So it remained through the extremely long reign of Victoria, then became His Majesty’s Theatre until the nearly as long reign of the present monarch, Elizabeth II, and it is now once again Her Majesty’s. It seems highly likely to change its name again when Charles or William takes over from Elizabeth, though long may she reign!

this theatre began its life as the Queen’s Theatre in 1705, named in honor of Queen Anne, who was the monarch at the time. But Handel wrote most of his operas during the reigns of George I and II, so the theatre’s name changed to The King’s. To continue what seems interesting to me and may or may not be to you, in 1837, when Victoria became queen, it was re-named again, but not the Queen’s

Theatre – instead it was puffed up a tad, and called Her Majesty’s Theatre. So it remained through the extremely long reign of Victoria, then became His Majesty’s Theatre until the nearly as long reign of the present monarch, Elizabeth II, and it is now once again Her Majesty’s. It seems highly likely to change its name again when Charles or William takes over from Elizabeth, though long may she reign!

Just across the street from the King’s, the Haymarket also became

important after 1766, but only in the summers, as we noted in the last lecture.

Before 1737 there were

several other small theatres in existence, but the Licensing Act shut them

down, at least temporarily.

|

| The Haymarket in 2012 |

Eighteenth century London theatres were built on the pit, box, and

gallery system. At the beginning of the century the stage was

nearly as deep as the auditorium, and half of the stage (the forestage) was in front of the proscenium arch, the other half (the scenic stage) behind that arch. Actors played on the forestage, scenic spectacle was confined to the area behind the proscenium. Stage seating continued until David Garrick stopped this practice in 1762. As greater numbers of audience members were packed into the theatres, the forestage began to be cut back to make room for more audience seating. Actor Colley Cibber criticized this cutting back of the acting space:

nearly as deep as the auditorium, and half of the stage (the forestage) was in front of the proscenium arch, the other half (the scenic stage) behind that arch. Actors played on the forestage, scenic spectacle was confined to the area behind the proscenium. Stage seating continued until David Garrick stopped this practice in 1762. As greater numbers of audience members were packed into the theatres, the forestage began to be cut back to make room for more audience seating. Actor Colley Cibber criticized this cutting back of the acting space:

“When the actors were in possession of

that forward space to advance upon, the Voice was more in the center of the

house...nor was the minutest motion of a Feature ever lost.”

As the forestage receded, actors got pushed upstage into the

scenery. During the eighteenth century, theatres became more than ever before

focused on scenic spectacle. As the auditoriums grew so did the vogue for

special effects such as conflagration and aquatic scenes that excited

audiences.

Throughout the century scenery was changed by the wing and groove

method, but early in the eighteenth century there wasn’t much need for

scene changes in a play. A stock interior or exterior did the trick, because

plays were constrained by the neoclassic unities, including the unity of

place. As the century progressed, however, more interest was taken

in “local color” in stage design; in other words, the depiction of specific

areas in a relatively accurate rendering. So even in single location

plays, settings began to get more complicated, more literal. And later in

the century, as opera and ballet featured sets that were changed in dazzling

manner, scene changes began to be incorporated in straight plays as well. So a

popular demand for scenery began to overrule neoclassic rules. Specific and

changeable scenery increased the need for a new-ish member of the creative team

– the scenic artist.

By far the most important scenic artist in 18th century

England was French: Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg (1740-1812). Famous

actor David Garrick brought De Loutherbourg to England in 1771, after he’d admired his designs at the Paris Opera. De Loutherbourg spent ten years at the Drury Lane Theatre and revolutionized design there. He oversaw ALL visual elements, and worked to unify the design concept for each play. He broke up the symmetrical look provided by wings and

shutters by placing ground rows and large set pieces on the stage floor. He worked with light to aid design rather than for mere illumination, and he took a strong interest in local color and increasing historically accuracy in settings, although this last aspect of design wasn’t fully exploited until the mid-nineteenth century.

actor David Garrick brought De Loutherbourg to England in 1771, after he’d admired his designs at the Paris Opera. De Loutherbourg spent ten years at the Drury Lane Theatre and revolutionized design there. He oversaw ALL visual elements, and worked to unify the design concept for each play. He broke up the symmetrical look provided by wings and

shutters by placing ground rows and large set pieces on the stage floor. He worked with light to aid design rather than for mere illumination, and he took a strong interest in local color and increasing historically accuracy in settings, although this last aspect of design wasn’t fully exploited until the mid-nineteenth century.

De Loutherbourg’s designs increasingly dominated the Drury Lane

stage, and became the focus of critical debate. His greatest and

most

unique scenic achievement came in Eidophysikon,

a production that took the ultimate step of dispensing altogether with script

and actors, and moved with grandeur from one scenic effect to the next. One writer called this the “spectaculist”

school of thought, and it hasn’t died out even today...their story, as usual,

is our story.

Lighting aided stage illusion increasingly in the late eighteenth century with the invention of the argand lamp, which ensured a brighter,

steadier light than candles could produce. As an example of the

increasing importance of lighting, in 1745 London theatres spent £340 a year on

lighting. Careful records were kept of all expenses. By the 1770s this

expenditure had increased to £1970 a year! Sadly, with the increased

interest in lighting came the increased chance of theatre fires. As a result,

in 1794 the gigantic new Drury Lane (rebuilt after a fire) was equipped with

the world’s first safety curtain, made of iron, and 14 years later with the

first sprinkler system.

Although De Loutherbourg and others strove to unify production

design, the costumes seldom fit in with the rest of the design concept – for

the most part, actors wore elegant contemporary clothing. In classics,

men resorted to habit à la Romaine

(dressed like a Roman). You’ll remember from earlier lectures that that odd

arrangement was a strange combination of contemporary wigs, boots and breeches

with pieces of Roman togas and tunics. Women usually added an exotic

touch or two in the areas of shoulders and/or waist to indicate a “classical “

look. Late in the century, attempts were made to make costumes fit the

period and the general design concept, but, largely because star performers did

what they liked, not until the mid 19th century was real historical

accuracy seen in costumes.

The Actors

And speaking of performers, while spectacle increased dramatically

on the eighteenth century stages, the actor became more than ever before

the center of theatrical attention. In the eighteenth century, we

enter the “age of the actor,” and it remains an “actor’s theatre” for nearly

two centuries. Let’s look at a few.

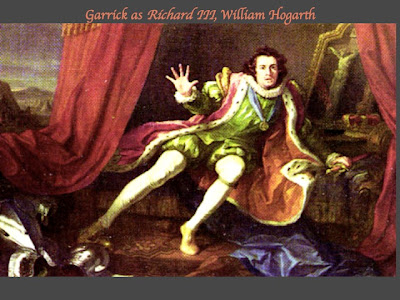

Colley Cibber was one of the first actor-managers. Cibber

began his career at the tail end of the Restoration, and eventually managed the

Drury Lane along with two other men. In addition to his managerial

duties, he wrote several plays including The

Careless Husband (discussed

briefly in an earlier lecture). But Cibber was best known for his acting. His

signature role was Richard III, whose dialogue he altered, padding this already

large role with speeches from Henry VI

part 3 and a number of speeches that Cibber wrote FOR himself! For one

famous example, at a point in the action Shakespeare has Richard say, “Off with

his head.” Cibber uses that phrase, but adds a rather chilling, “So much

for Buckingham.” Later actors down to Laurence Olivier kept this line in

though they got rid of most of Cibber’s “improvements.” In this case

Shakespeare was improved not for poetic justice as Nahum Tate’s awful King Lear had done, but to pad the role

of the star: “Off with his head...so much for Buckingham.” And so much, I fear,

for Shakespeare!

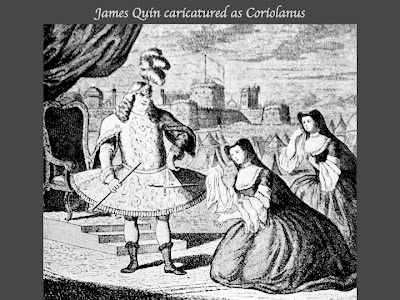

James Quin was the most popular actor in London in the first half

of the eighteenth century. He performed at Drury Lane until he was

overwhelmed by the arrival of David Garrick. Quin made an excellent Falstaff, apparently, but his Othello, said one critic, could never really have won Desdemona. His style was, simply put, loud, strong, declamatory, but while audiences thrilled at his bombastic manner, it didn’t always work so well. Critic Tobias Smollett liked Quinn in a number of roles, but had this to say about his Brutus: He shows his despair

overwhelmed by the arrival of David Garrick. Quin made an excellent Falstaff, apparently, but his Othello, said one critic, could never really have won Desdemona. His style was, simply put, loud, strong, declamatory, but while audiences thrilled at his bombastic manner, it didn’t always work so well. Critic Tobias Smollett liked Quinn in a number of roles, but had this to say about his Brutus: He shows his despair

“by beating his own forehead and

bellowing like a bull; and indeed, in almost all his most interesting scenes,

performs such strange shakings of the head and other antic gesticulations, that

when I first saw him act, I imagined the poor man laboured under [a]

paralytical disorder.” (qtd in Nagler, Sourcebook in Theatrical History)

So much for Quin!

Charles Macklin was known primarily for transforming Shylock in

the Merchant of Venice. Up until this

time, Shylock had been

played in broad and caricatured strokes, with a false hooked nose and red beard. Macklin dressed himself as a respectable merchant, did away with false appendages and made Shylock a somewhat sympathetic character – nothing like he’s portrayed now, but a bold stroke in an age where “outsiders” such as Jews were not popular.

played in broad and caricatured strokes, with a false hooked nose and red beard. Macklin dressed himself as a respectable merchant, did away with false appendages and made Shylock a somewhat sympathetic character – nothing like he’s portrayed now, but a bold stroke in an age where “outsiders” such as Jews were not popular.

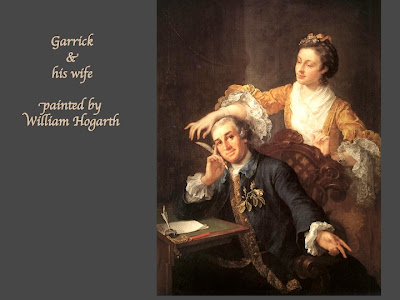

David Garrick toppled Quin and Macklin from power in the 1740s and

overshadowed all other eighteenth century British actors. He wanted

at first to be a wine merchant, and that’s why he journeyed to London at age

20. But once there he fell in love with the theatre. He made his

professional debut 1741, playing Richard III, and knocked out his audiences.

He was invited to become a member of the company at Drury Lane, and in 1747 he began

to manage it.

As a manager Garrick banned stage seating, placed De Loutherbourg

in charge of design, and ran a tight, well-organized ship. Garrick also took to

directing plays that he starred in.

“Directing” is a rather loose term. There weren’t many rehearsals in the eighteenth century, and those few focused on ensuring that the star was at center stage, but Garrick rehearsed his actors harder and longer than anyone had before. In addition to all this, Garrick was a fairly good writer/ adapter, particularly in comic afterpieces such as Miss in Her Teens (1774). He also trimmed Shakespeare to play as afterpieces: Catherine and Petruchio and Florizel and Perdita (1756) are examples.

“Directing” is a rather loose term. There weren’t many rehearsals in the eighteenth century, and those few focused on ensuring that the star was at center stage, but Garrick rehearsed his actors harder and longer than anyone had before. In addition to all this, Garrick was a fairly good writer/ adapter, particularly in comic afterpieces such as Miss in Her Teens (1774). He also trimmed Shakespeare to play as afterpieces: Catherine and Petruchio and Florizel and Perdita (1756) are examples.

As an actor, Garrick was said to have been much more “natural”

than other actors of his time. This wouldn’t have been too hard to manage when

you consider the ravings of Quin, but I’m not certain

that Stanislavsky would have approved. One of Garrick’s tricks was to wear a “fright wig” as Hamlet, when he first sees his father’s spirit – his hair hangs naturally early in the scene -- but then Garrick worked a device in his pocket that caused the hair to stick out in a frightening manner; you might say that he “wigs out! ” Whether or not Stanislavsky would have liked loved it, Garrick’s audiences did – when Garrick played, money was made! The eighteenth century British theatre is often called the Age of Garrick.

that Stanislavsky would have approved. One of Garrick’s tricks was to wear a “fright wig” as Hamlet, when he first sees his father’s spirit – his hair hangs naturally early in the scene -- but then Garrick worked a device in his pocket that caused the hair to stick out in a frightening manner; you might say that he “wigs out! ” Whether or not Stanislavsky would have liked loved it, Garrick’s audiences did – when Garrick played, money was made! The eighteenth century British theatre is often called the Age of Garrick.

Garrick had many leading ladies, among them Mrs. Pritchard, who

was noted for the wide variety of roles she was able to play.

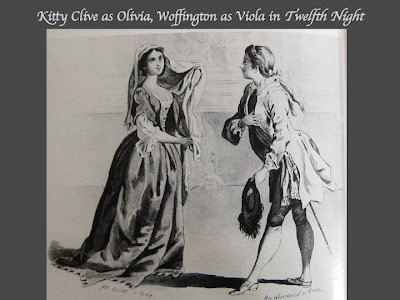

Two other talented and flamboyant actresses, Margaret “Peg” Woffington and George Anne Bellamy, partnered with Garrick,

Woffington not only on the boards but between the sheets! Peg Woffington was perhaps the best known of all eighteenth century actresses, at least before Mrs. Siddons rose to fame and ruled the stage at the end of the century. Sadly, Peg died before she reached forty. Among her roles were Polly in The Beggar’s Opera, and Ophelia.

Two other talented and flamboyant actresses, Margaret “Peg” Woffington and George Anne Bellamy, partnered with Garrick,

Woffington not only on the boards but between the sheets! Peg Woffington was perhaps the best known of all eighteenth century actresses, at least before Mrs. Siddons rose to fame and ruled the stage at the end of the century. Sadly, Peg died before she reached forty. Among her roles were Polly in The Beggar’s Opera, and Ophelia.

One of Woffington’s major rivals was George Anne Bellamy.

Bellamy also played frequently with Garrick, including as Juliet to

his Romeo during an interesting twelve-night feud in 1750. Garrick and Bellamy played the roles at the Drury Lane on the same nights that Garrick’s rival Spranger Barry and Susannah Cibber played them at Covent Garden. After the twelfth night (no pun intended) of this rivalry Barry and Cibber threw in the towel, to everyone’s relief. The theatre-going public was used to rotating rep, and they attended the theatre regularly, so the same play to run consecutively for nearly two weeks in both legitimate theatres must have been irritating. It certainly seems so in a little ditty on the subject published in the Daily Advertiser:

his Romeo during an interesting twelve-night feud in 1750. Garrick and Bellamy played the roles at the Drury Lane on the same nights that Garrick’s rival Spranger Barry and Susannah Cibber played them at Covent Garden. After the twelfth night (no pun intended) of this rivalry Barry and Cibber threw in the towel, to everyone’s relief. The theatre-going public was used to rotating rep, and they attended the theatre regularly, so the same play to run consecutively for nearly two weeks in both legitimate theatres must have been irritating. It certainly seems so in a little ditty on the subject published in the Daily Advertiser:

“Well, what tonight?” says angry Ned

As up from bed he rouses;

“Romeo again!” and shakes his head –

A plague on both your houses!

Bellamy wrote her memoirs (mostly about her many love affairs but

a little about her life on the stage as well) a few years before her death in

1788. She recounts many stories that attest to the

outrageous liberties star actors took with costuming, just so they could look good. One particular story involves her rivalry with Peg Woffington and shows how nasty the world of theatre can become when egos get in the way. Woffington was thought to have the greater talent, but Bellamy was quite beautiful, and used her ability to look good en costume as a way of evening the scales. She speaks, in painstaking detail, of a production at Covent Garden early in 1756, in which she and Woffington were cast as two rival queens I have trimmed it considerably. DO read it, as I at least think it’s worth it:

outrageous liberties star actors took with costuming, just so they could look good. One particular story involves her rivalry with Peg Woffington and shows how nasty the world of theatre can become when egos get in the way. Woffington was thought to have the greater talent, but Bellamy was quite beautiful, and used her ability to look good en costume as a way of evening the scales. She speaks, in painstaking detail, of a production at Covent Garden early in 1756, in which she and Woffington were cast as two rival queens I have trimmed it considerably. DO read it, as I at least think it’s worth it:

The animosity this lady had long borne

me had not experienced any decrease. On the contrary, my late additional

finery in my jewels, etc, had augmented it to something very near hatred.

My royal robes were showy and proper for

the character – taste and elegance were never so happily blended, especially in

one of them, the ground of which was deep yellow. Mr. Rich had purchased

a suit of her royal highness’s…for Mrs Woffington. It…looked very

beautiful by day-light; but…it appeared to be a dirty white, by candle-light,

especially when my splendid yellow was next to it. To [my] dress I had

added a purple robe;…[which] made it appear, if possible, to greater advantage!

Thus accoutred in my magnificence, I

made my entree into the Green Room…As soon as she saw me, almost bursting with

rage, she drew herself up, and thus…addressed me, “I desire, Madam, you will

never more, upon any account, wear those clothes in the piece we perform

tonight.” I replied, “I know not, madam,

by what right you take upon you to dictate to me what I shall wear. And I

assure you, Madam, that you must ask it in a very different manner, before you

obtain my compliance.” She now found it necessary to solicit in a softer

strain. And I readily gave my assent…

However, the next night I sported my

other suit; which was much more splendid than the former. This rekindled

Mrs Woffington’s rage, so that it nearly bordered on madness. When, oh!

dire to tell! she drove me off the carpet!…

Though I despise revenge, I do not

dislike retaliation. I therefore put on my yellow…once more. As

soon as I appeared in the Green room her fury could not be kept within

bounds! His excellency the Comte de Haslang stopped my enraged rival’s

pursuit: I should have otherwise stood a chance of appearing in the next

scene with black eyes, instead of the blue ones which nature had given me.

(qtd in Nagler, Sourcebook

in Theatrical History)

Another rival of Woffington’s was Kitty Clive. Peg and Kitty

played together frequently and stories are told about their battles on and off

the stage, similar to Woffington’s and Bellamy’s.

Finally, a young woman named Mary Robinson, regarded as one of the

most beautiful women in late eighteenth century London, was trained

by Garrick to play Cordelia to his Lear, and was featured by the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan when he took over management of the Drury Lane. She shone so particularly in Garrick’s shortened adaptation of Winter’s Tale that she was known around town as “Perdita,” and became the first mistress to the Prince of Wales, who later became King George IV of England. A happy ending, a la Nell Gwyn? No indeed, sad to say. While Mrs Robinson was the regent’s first mistress he soon turned her out for another, and her life became quite miserable thereafter.

by Garrick to play Cordelia to his Lear, and was featured by the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan when he took over management of the Drury Lane. She shone so particularly in Garrick’s shortened adaptation of Winter’s Tale that she was known around town as “Perdita,” and became the first mistress to the Prince of Wales, who later became King George IV of England. A happy ending, a la Nell Gwyn? No indeed, sad to say. While Mrs Robinson was the regent’s first mistress he soon turned her out for another, and her life became quite miserable thereafter.

During the eighteenth century the business of the theatre

becomes very important, and we begin to get detailed records of different

theatres’ profits and losses, salary scales, etc. The players were

rigidly structured into “lines of business.”

1. stars

2. leading roles

3. supporting

players (usually “character” specialists

4. “walking

ladies and gentlemen”

5. “fifth

business” -- walk ons! supers!

Theatre in London during the eighteenth century was a frankly

commercial enterprise, not an art theatre.

David Garrick, like other theatrical managers of the day, recognized

that theatre was a business, and that its main business was to place, as the

saying goes, buns in the seats. A typical poetical thought from this century,

in neoclassic rhymed couplets, comes from Samuel Johnson, on the occasion of

the re-opening of the Drury Lane in September 1747:

The drama’s laws, the drama’s patrons give

for we that live to please, must please to live

qtd in The Theatrical Public in the Time of Garrick.

Next up, after a semester break, we'll look at theatre in eighteenth century France!

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1954. p 134)