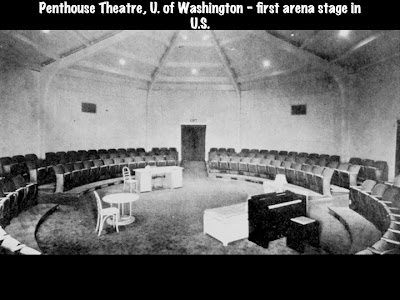

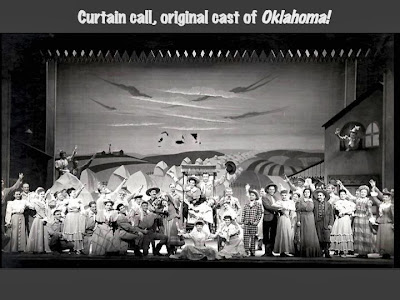

The commercial theatre began to produce more musicals than plays beginning in the 1950s, and what plays were offered were those that could be nearly certain of financial success. Many serious theatre artists reacted by moving away from, or “Off“ Broadway, and focused on non-commercial plays including classics, pieces from the modern European repertoire, and new American plays. The theatres they performed in were more intimate and configured differently from the proscenium arch Broadway theatres; either thrust stages, in which the stage literally thrust out into an audience seated three-quarters around it, or arena stages, in which the audience completely surrounded the action.

An early example was The

American Repertory Theatre of Eva LeGallienne, Margaret Webster, and the

ubiquitous Cheryl Crawford. It lasted only one season, 1946-47, but paved

the way for other experimental groups. By 1955-56, more than 90

“off-Broadway” groups had formed in New York City. The most important was The Circle in the Square, founded in

1951. Located in Greenwich Village at Sheridan Square, it was run by Jose Quintero and Theodore Mann. In

the second season, Quintero’s production of Summer

and Smoke put the theatre on the map; in 1956 Quintero’s brilliant

production of The Iceman Cometh

cemented its reputation. Actors included Jason Robards Jr, George C. Scott and

Colleen Dewhurst among many others.

In 1953 T. Edward Hambleton and Norris Houghton formed the Phoenix

Theatre, where most of the plays were staged by

director Stuart Vaughn. This company featured a tremendously diverse repertoire, and a fine permanent acting company. In the early 60s the Phoenix joined forces with A.P.A. (Association of Producing Artists) led by actor/director Ellis Rabb, and as the APA/Phoenix it presented beautiful and smart productions from the classic and modern European repertoire.

director Stuart Vaughn. This company featured a tremendously diverse repertoire, and a fine permanent acting company. In the early 60s the Phoenix joined forces with A.P.A. (Association of Producing Artists) led by actor/director Ellis Rabb, and as the APA/Phoenix it presented beautiful and smart productions from the classic and modern European repertoire.

In 1963 the Lincoln Center

for the Performing Arts was formed. This plaza united four buildings that

showcased all the performing arts, opera, ballet, classical music, and of

course the theatre. Unfortunately the Vivian Beaumont theatre at Lincoln

Center, whose backstage could house

settings for three plays which could run in rotating rep, seemed jinxed. Several fine artistic directors failed to create successful seasons there until in the mid-80s Gregory Mosher brought life into it with a terrific revival of Anything Goes and ran it for three years. This compromised the mission but saved the theatre. Since then smart revivals of famous American plays (The Little Foxes, A Delicate Balance), occasional new American plays (Six Degrees of Separation), classics and modern European plays (Twelfth Night with Helen Hunt, Chekhov’s Ivanov, with Kevin Kline, Stoppard’s Arcadia & Coast of Utopia), enjoyed some success and very recently South Pacific and now War Horse have been extremely popular.

settings for three plays which could run in rotating rep, seemed jinxed. Several fine artistic directors failed to create successful seasons there until in the mid-80s Gregory Mosher brought life into it with a terrific revival of Anything Goes and ran it for three years. This compromised the mission but saved the theatre. Since then smart revivals of famous American plays (The Little Foxes, A Delicate Balance), occasional new American plays (Six Degrees of Separation), classics and modern European plays (Twelfth Night with Helen Hunt, Chekhov’s Ivanov, with Kevin Kline, Stoppard’s Arcadia & Coast of Utopia), enjoyed some success and very recently South Pacific and now War Horse have been extremely popular.

Outside of New York City, tours of commercial theatre were the

rule until intrepid pioneers began to form

the first “regional” theatres, which

were usually thrust or arena

stages. Like Off- Broadway, these theatres featured an alternative to safe commercial fare: a mix of modern European and classic plays, and new, often experimental American plays. Margo Jones (1913-1955) created an arena stage at Dallas in 1947, where she focused on producing new American plays. Her book Theatre-in-the-Round (1951) inspired others to attempt

alternative theatre in unique and different spaces. Jones’s first disciple was Nina Vance (1914-1980), working in nearby Houston. She created the Alley Theatre, also in 1947, another theatre in the round. The Alley Theatre is thriving today, one of the most impressive and long-lived regional theatres in America. Arena Stage in Washington DC was founded by Zelda Fichandler (1924- ), a graduate student at George Washington University in 1950. Zelda and her husband Tom became the artistic and managing directors, respectively, and ran Arena Stage for 40 years before placing it in the hands of others.

stages. Like Off- Broadway, these theatres featured an alternative to safe commercial fare: a mix of modern European and classic plays, and new, often experimental American plays. Margo Jones (1913-1955) created an arena stage at Dallas in 1947, where she focused on producing new American plays. Her book Theatre-in-the-Round (1951) inspired others to attempt

alternative theatre in unique and different spaces. Jones’s first disciple was Nina Vance (1914-1980), working in nearby Houston. She created the Alley Theatre, also in 1947, another theatre in the round. The Alley Theatre is thriving today, one of the most impressive and long-lived regional theatres in America. Arena Stage in Washington DC was founded by Zelda Fichandler (1924- ), a graduate student at George Washington University in 1950. Zelda and her husband Tom became the artistic and managing directors, respectively, and ran Arena Stage for 40 years before placing it in the hands of others.

|

| Design for an arena stage can be simple, but not necessarily! |

organization for the regional theatre movement. In 1963, as a result, famed British director Tyrone Guthrie opened a theatre in Minneapolis called The Guthrie, modeled on his earlier thrust stage in Stratford, Ontario. The same year, Baltimore Center Stage and the Seattle Repertory Theatre were founded. The next year Actors Theatre of Louisville and Hartford Stage Company in Connecticut joined them, and in 1965 San Francisco’s A.C.T. and New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre were created.

Other distinguished members of this theatrical community include

Yale Rep, also in New Haven, the McCarter Theatre in Princeton New Jersey, the

American Repertory Theatre (ART) in Cambridge Massachusetts,

Trinity Rep in Providence Rhode Island, the Goodman (along with many smaller theatres) in Chicago, the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and South Coast Rep in Costa Mesa California. In spite of constant funding problems, the regional theatre movement has grown to more than 200 theatres. Among them they offer thousands of productions a year to tens of thousands of people all over America, and have become what some critics have termed our “national” theatre.

Trinity Rep in Providence Rhode Island, the Goodman (along with many smaller theatres) in Chicago, the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and South Coast Rep in Costa Mesa California. In spite of constant funding problems, the regional theatre movement has grown to more than 200 theatres. Among them they offer thousands of productions a year to tens of thousands of people all over America, and have become what some critics have termed our “national” theatre.

By the early 1960s in New York, the Off-Broadway movement had begun,

in the eyes of some viewers, to show signs of becoming institutionalized and

respectable. The Off-Off Broadway movement was created in reaction, to provide

new and more experimental works in non-traditional spaces. This experimentation took many forms. The Caffe Cino is usually thought of as the first important performance space in the movement. Located in Greenwich Village, as were all the early Off-Off Broadway theatres, Caffe Cino was not a theatre, but a coffeehouse opened by Joe Cino in late 1958 in which artists could attempt whatever they wanted. The usual entertainment was music and poetry readings on a tiny, slightly raised stage, until one night someone decided to read a play aloud. From this grew productions of much new and unusual theatrical fare, including some of the first plays by Lanford Wilson, Maria Irene Fornes and John Guare.

new and more experimental works in non-traditional spaces. This experimentation took many forms. The Caffe Cino is usually thought of as the first important performance space in the movement. Located in Greenwich Village, as were all the early Off-Off Broadway theatres, Caffe Cino was not a theatre, but a coffeehouse opened by Joe Cino in late 1958 in which artists could attempt whatever they wanted. The usual entertainment was music and poetry readings on a tiny, slightly raised stage, until one night someone decided to read a play aloud. From this grew productions of much new and unusual theatrical fare, including some of the first plays by Lanford Wilson, Maria Irene Fornes and John Guare.

A bit farther east in the Village, at Washington Square Park, the

Reverend Al Carmines (1938- ) opened the

Judson Memorial Church to performing artists.

Also renowned for hosting early postmodern dance performance, throughout

the 1960s the Church housed the Judson

Poets’ Theatre, which produced a series of countercultural plays and

musicals supported by its hip congregation.

One of the more successful pieces to come from this theatre was

Carmine’s own musical version of the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata, called Peace,

and written in 1968 to coincide with the Paris Peace talks on the Vietnam War.

Still farther east in Greenwich Village, Ellen Stewart (1921- ) started her own café/theatre known by her

own nickname:

La Mama. Stewart rang a bell at the beginning of each evening’s performance and announced that the cafe was home to playwrights and all other theatre lovers. Admission was whatever you could afford. Eventually Stewart settled in a space on East 4th street, where La Mama ETC (Experimental Theatre Club) is still alive and productive. La Mama introduced the plays of Sam Shepard, Julie Bovasso, and Harvey Fierstein. Directors such as Richard Foreman, Meredith Monk and Ping Chong began their careers here. International artists such as Jerzy Grotowski and Andrei Serban were also welcomed at this vital venue for experimental theatre and performance art.

La Mama. Stewart rang a bell at the beginning of each evening’s performance and announced that the cafe was home to playwrights and all other theatre lovers. Admission was whatever you could afford. Eventually Stewart settled in a space on East 4th street, where La Mama ETC (Experimental Theatre Club) is still alive and productive. La Mama introduced the plays of Sam Shepard, Julie Bovasso, and Harvey Fierstein. Directors such as Richard Foreman, Meredith Monk and Ping Chong began their careers here. International artists such as Jerzy Grotowski and Andrei Serban were also welcomed at this vital venue for experimental theatre and performance art.

The Living

Theatre, founded by Julian Beck

(1925-1985) and Judith Malina

(1926- ), provided the most radical

experiments in the Off-Off Broadway movement. Begun in the early 1950s to produce poetic, avant-garde drama, by late in that decade the group shifted focus and began to use improvisation to create events which stressed total freedom, offering anti-establishment messages and communing and interacting with audiences. In 1968, the

Living Theatre offered its most famous production, Paradise Now, which broke down all barriers between actors and audience. The actors stripped and some of the audience stripped as well. They danced together naked. Actors and audience often danced out of the performance space and out into the streets, where the company was frequently arrested for indecent exposure. Beck and Malina welcomed the arrests, which, they argued, showed the repressive nature of traditional authority figures who attempt to limit personal freedom. The Living Theatre was criticized by many, even among the theatrical avant-garde, but in its heyday, the group pioneered the breaking of barriers between actor and audience, art and life, dramatic action and social action. It was revolution as theatre, and theatre as revolution.

experiments in the Off-Off Broadway movement. Begun in the early 1950s to produce poetic, avant-garde drama, by late in that decade the group shifted focus and began to use improvisation to create events which stressed total freedom, offering anti-establishment messages and communing and interacting with audiences. In 1968, the

Living Theatre offered its most famous production, Paradise Now, which broke down all barriers between actors and audience. The actors stripped and some of the audience stripped as well. They danced together naked. Actors and audience often danced out of the performance space and out into the streets, where the company was frequently arrested for indecent exposure. Beck and Malina welcomed the arrests, which, they argued, showed the repressive nature of traditional authority figures who attempt to limit personal freedom. The Living Theatre was criticized by many, even among the theatrical avant-garde, but in its heyday, the group pioneered the breaking of barriers between actor and audience, art and life, dramatic action and social action. It was revolution as theatre, and theatre as revolution.

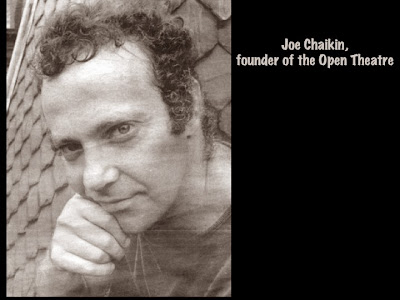

Joseph Chaikin (1935-2003), a

former member of the Living Theatre, developed his own explorations of acting

style and collaborative creation. He founded the Open Theatre

in 1963 as a collective for theatre artists. Chaikin’s major theories included “presence,” in which the performer, not the character, is the center of focus; and “transformation,” in which the actor changes from one role to another before the audience’s eyes. One of the most important theatrical creations to evolve from Chaikin’s method was The Serpent (1968), an exploration of Adam, Eve, and the fall from grace. The Open Theatre critiqued American society and the Viet Nam war, in a daring and highly professional theatrical style. It was one of the most honored American experimental groups.

in 1963 as a collective for theatre artists. Chaikin’s major theories included “presence,” in which the performer, not the character, is the center of focus; and “transformation,” in which the actor changes from one role to another before the audience’s eyes. One of the most important theatrical creations to evolve from Chaikin’s method was The Serpent (1968), an exploration of Adam, Eve, and the fall from grace. The Open Theatre critiqued American society and the Viet Nam war, in a daring and highly professional theatrical style. It was one of the most honored American experimental groups.

Since the 1960s and 70s, the terms Off-Broadway and

Off-Off-Broadway have come to refer more to kinds of Actors Equity contracts

than movements for artistic and political change. It is in these theatres, however, and not in

the commercial theatrical scene, that most important new American drama is

being nurtured.

Several non-profit producing organizations that have become vital

to the American theatre were formed in Manhattan in the late 1960s and early

1970s. The earliest of these was the Roundabout

Theatre, formed by Gene Feist in

1965 to give classic plays from the ancient to modern repertoire smart

productions by the finest current directors, designers and actors. The theatre

received many awards in its first 20 years, but found itself losing money. In

1989 Gene Feist

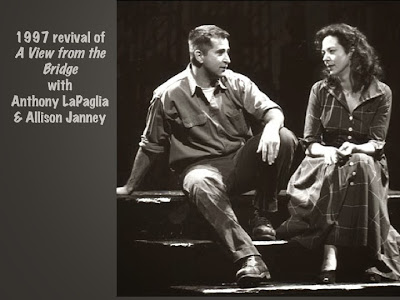

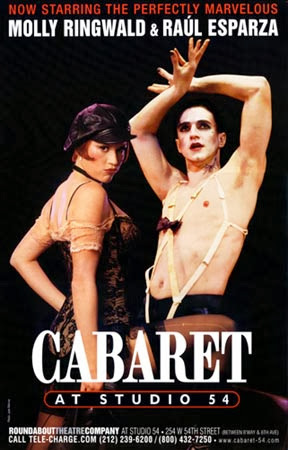

retired and turned over the theatre to Todd Haimes, who has run the Roundabout since then. Haimes reached out in a number of different directions, offering such diverse writers as Moliére, Eugene O’Neill, Harold Pinter, and Arthur Miller, alongside successful revivals of musicals including She Loves Me, which moved to Broadway, and Cabaret, which moved to Studio 54 and became a huge

moneymaker for this theatre. In 2000, the Roundabout added a location on 42nd Street, their first show there the American classic comedy The Man Who Came to Dinner. In 2004 it revived to critical acclaim Stephen Sondheim’s disturbing musical Assassins. Its location is in the center of the commercial theatre district, and its recent production history reflects a delicate balance between commercial hits, classic plays, and tough new fare from the likes of Irish playwright Martin McDonagh.

retired and turned over the theatre to Todd Haimes, who has run the Roundabout since then. Haimes reached out in a number of different directions, offering such diverse writers as Moliére, Eugene O’Neill, Harold Pinter, and Arthur Miller, alongside successful revivals of musicals including She Loves Me, which moved to Broadway, and Cabaret, which moved to Studio 54 and became a huge

moneymaker for this theatre. In 2000, the Roundabout added a location on 42nd Street, their first show there the American classic comedy The Man Who Came to Dinner. In 2004 it revived to critical acclaim Stephen Sondheim’s disturbing musical Assassins. Its location is in the center of the commercial theatre district, and its recent production history reflects a delicate balance between commercial hits, classic plays, and tough new fare from the likes of Irish playwright Martin McDonagh.

The Manhattan

Theatre Club (MTC) has followed somewhat in the footsteps of The Roundabout,

although whereas the Roundabout’s prime focus is on established plays and

playwrights, MTC favors new writers from the

United States and abroad. Founded in 1970 by a collective team, it has been run since 1972 by Lynne Meadow. MTC has been much praised and in 1977 received an Obie (Off-Broadway award) for Sustained Excellence. In 1989 it was given a Drama Desk award for its high standards, its encouragement of new playwrights, and for its importations from abroad.

Among its many distinguished writers are August Wilson, Beth Henley, Donald Margulies, and its most frequently produced playwright, Terrence McNally. Three of its plays have received Pulitzer Prizes, most recently John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt. MTC has moved several plays to Broadway and now boasts a permanent Broadway theatre, The Biltmore, in addition to its two spaces just off Broadway on 55th Street. Like the Roundabout, MTC straddles the worlds of commercial and non-profit theatre.

United States and abroad. Founded in 1970 by a collective team, it has been run since 1972 by Lynne Meadow. MTC has been much praised and in 1977 received an Obie (Off-Broadway award) for Sustained Excellence. In 1989 it was given a Drama Desk award for its high standards, its encouragement of new playwrights, and for its importations from abroad.

Among its many distinguished writers are August Wilson, Beth Henley, Donald Margulies, and its most frequently produced playwright, Terrence McNally. Three of its plays have received Pulitzer Prizes, most recently John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt. MTC has moved several plays to Broadway and now boasts a permanent Broadway theatre, The Biltmore, in addition to its two spaces just off Broadway on 55th Street. Like the Roundabout, MTC straddles the worlds of commercial and non-profit theatre.

In 1971 Robert Moss

founded Playwrights Horizons as a

place to develop and produce new scripts. He located it in a run-down area on

far west 42nd that came to be known as

Theatre Row when a number of other intimate theatres joined it in the 1970s and 80s. This company has produced more than 350 new playwrights, and has work-shopped many more. Its most successful authors include Christopher Durang, Wendy Wasserstein, and A.R. Gurney. Four plays produced at Playwrights Horizons have won Pulitzer Prizes, including Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife

in 2004. Playwrights Horizons has also launched musicals, including Once on this Island, Falsettos, and Sondheim’s extraordinary Sunday in the Park with George, all of which have transferred to Broadway. Current artistic director Tim Sandford was responsible for moving Playwrights Horizons into a new space in 2003, on a refurbished and gentrified Theatre Row. Current artistic director Tim Sandford was responsible for moving Playwrights Horizons into a new space in 2003.

Theatre Row when a number of other intimate theatres joined it in the 1970s and 80s. This company has produced more than 350 new playwrights, and has work-shopped many more. Its most successful authors include Christopher Durang, Wendy Wasserstein, and A.R. Gurney. Four plays produced at Playwrights Horizons have won Pulitzer Prizes, including Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife

in 2004. Playwrights Horizons has also launched musicals, including Once on this Island, Falsettos, and Sondheim’s extraordinary Sunday in the Park with George, all of which have transferred to Broadway. Current artistic director Tim Sandford was responsible for moving Playwrights Horizons into a new space in 2003, on a refurbished and gentrified Theatre Row. Current artistic director Tim Sandford was responsible for moving Playwrights Horizons into a new space in 2003.

Director Marshall Mason,

playwright Lanford Wilson and others

founded the Circle Rep in 1969 to

focus on the relationship between actor and playwright. This downtown

theatre, only a short distance from the original Circle in the Square, established workshops for new American writers. In these workshops a body of actors, directors, designers and dramaturgs supported the plays. Certainly the most famous playwright to emerge from Circle Rep was Wilson, but new plays by several other increasingly important writers built its reputation. The Circle Rep was honored in 1991 with Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Body of Work. Ironically, only a few years later the organization shut down for lack of funds, but in its more than 20 years the group built a reputation for staging fine new American plays, smartly acted, directed and designed.

theatre, only a short distance from the original Circle in the Square, established workshops for new American writers. In these workshops a body of actors, directors, designers and dramaturgs supported the plays. Certainly the most famous playwright to emerge from Circle Rep was Wilson, but new plays by several other increasingly important writers built its reputation. The Circle Rep was honored in 1991 with Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Body of Work. Ironically, only a few years later the organization shut down for lack of funds, but in its more than 20 years the group built a reputation for staging fine new American plays, smartly acted, directed and designed.

Joseph Papp (1921-91) was

the last of the great American producer/ directors. Papp began a

Shakespeare Theatre Workshop in the Lower East Side in 1953, which in 1954

became the New York Shakespeare Festival. Papp

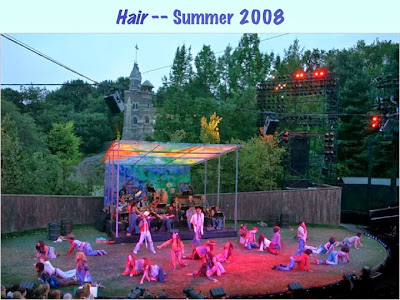

desired a fine professional theatre that would be free to the public, as in his words, a public library was. He fought City Hall until in 1957 he secured a permanent outdoor summer theatre, the Delacorte, in Central Park. Papp used flatbed trucks to carry Shakespeare to other city parks, presenting free Shakespeare to thousands, many of whom had never seen a play. In important addition to playing

Shakespeare, Papp has been responsible for producing minority writers’ works, including Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf in 1976 and George C. Wolfe’s The Colored Museum in 1986. He has funded and presented visiting artists and foreign works, including American premieres of Czech writer Vaclav Havel and British playwrights Caryl Churchill and David Hare. He has sponsored tiny musicals that became huge successes, for example Hair and A Chorus Line. Profits from Papp’s hit shows always went to back into his theatre to fund experimental and minority projects.

became the New York Shakespeare Festival. Papp

desired a fine professional theatre that would be free to the public, as in his words, a public library was. He fought City Hall until in 1957 he secured a permanent outdoor summer theatre, the Delacorte, in Central Park. Papp used flatbed trucks to carry Shakespeare to other city parks, presenting free Shakespeare to thousands, many of whom had never seen a play. In important addition to playing

Shakespeare, Papp has been responsible for producing minority writers’ works, including Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf in 1976 and George C. Wolfe’s The Colored Museum in 1986. He has funded and presented visiting artists and foreign works, including American premieres of Czech writer Vaclav Havel and British playwrights Caryl Churchill and David Hare. He has sponsored tiny musicals that became huge successes, for example Hair and A Chorus Line. Profits from Papp’s hit shows always went to back into his theatre to fund experimental and minority projects.

In 1967 Papp opened a permanent space at Astor Place, the Public Theatre, which contains several

performance spaces in several different configurations. He made enemies during his career and was

criticized at times for the quality of his productions, but as a theatre artist

he was bold, daring, unafraid and generous. Papp bequeathed the Public Theatre

to Joanne Akalaitis, a director

whose avant-garde productions proved so unpopular that she was forced out only

a year after Papp’s death. George

C. Wolfe took over in 1993 and successfully ran the theatre until the

spring of 2004, when he stepped down. Oskar

Eustis is the current director.

Papp was a defender of human rights. In a 1958 special Tony

award he was cited as one who was “driven to create theatre without regard for

cost or human interference.” He refused that year to name names before

the House Un-American Activities Committee, and late in his life (1990) he

rejected $748,000 from the NEA, though he could certainly have made use of the

money, because of an “anti-obscenity” pledge contained in the grant.

Here’s to more theatre artists might be as bold, daring, unafraid and generous

as was Joseph Papp...let his story be YOUR story.

******

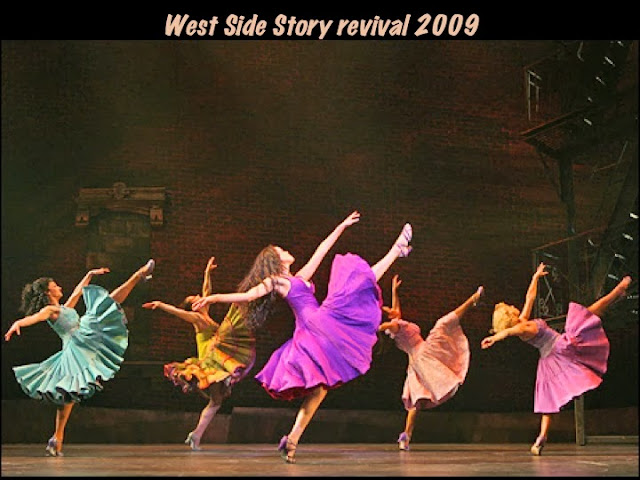

Theatre in the United States and around the world has been

frequently been pronounced “dead,” and indeed in an era that values computers

and television monitors, live performance can seem like an endangered

species. Postmodernists have blended

live performance with video and other media to bring it into the twenty-first century. Makers of musical theatre have adapted movies and have staged songs by

pop entertainers in order to hold onto audiences. Directors of Shakespeare and

other classics have modernized these works to reach out to youthful spectators.

As this brief history has attempted to show, theatre, the “fabulous

invalid,” continues to exist, because it is a wonderful way for people to come

together in a thoroughly “live” way to reach out to each other and celebrate

humanity. Certainly the theatre will continue to change, as it has throughout

the centuries, but it will always be informed by its amazing and exciting past,

as we have seen this year. The “invalid” can survive and flourish, because it

has always been, remains and I hope always will be one of most vital ways for

humans to hold a mirror up to nature.

That's the end of the course as I taught it at Ithaca College, but it's not quite the end here. There are a number of events in recent American theatre that I could never get to in Theatre History, but that I did cover in another course I taught, Contemporary Developments in Theatre. Next time, in the last lecture, a brief look at some of them, including multicultural theatre...

De Nobis, Fabula Narratur

That's the end of the course as I taught it at Ithaca College, but it's not quite the end here. There are a number of events in recent American theatre that I could never get to in Theatre History, but that I did cover in another course I taught, Contemporary Developments in Theatre. Next time, in the last lecture, a brief look at some of them, including multicultural theatre...