World War II caused even more destruction of life and land than had the first. By its end, Russia alone had lost more lives than the entire casualty count of the First World War. Germany had to be rebuilt from the ground up. Other countries of continental Europe found themselves in similar situations. Parts of England, for example, endured German bombing raids nearly every day for years. France capitulated and formed the Vichy government, friendly to the Nazis. Communist and Capitalist governments vied for control of the defeated countries, leaving Germany deeply divided and Eastern Europe cut off from the West. The United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, wreaking catastrophic havoc – they were unfathomable in their destructive power. A “cold” war began, primarily between the United States and the Soviet Union, forcing nearly every country on earth to align itself with one or the other of these two formidable and potentially deadly powers. When the cold war ended in 1989, even more difficult to resolve conflicts sprang up and continue. Serious artists wrestled with the strange paradox of the twentieth century: the more we advance, the more we destroy. Theatre and other arts began to examine grave questions about guilt and responsibility. Some artists went further, considering and depicting the world as a madhouse.

Theatrically, the clearest manifestation

of this confusion occurred in writers the critic Martin Esslin lumped together

in a group he called Theatre of the

Absurd. Esslin, an

English writer, producer, and critic, was born in 1918 in Budapest, grew up in Vienna but fled in 1938.

The absurd is not a movement of artists who held certain beliefs,

met together, and wrote manifestos, as had the dadaists, surrealists,

etc. This is a term coined by a scholar/critic to try to pull together a

sense of organization to plays that were deliberately DIS-organized, plays that

seemed to defy categorization.

Esslin saw the roots of the

absurd in Alfred Jarry’s King Ubu

and in the plays of Pirandello, which constantly questioned what was truth and

what illusion. Esslin identified the existential

playwrights Jean Paul Sartre and Albert Camus as more recent

influences. While these two writers differed in the details of their

work, they created the philosophic base: Sartre wrote novels, essays and plays such as The Flies (1943) and No Exit

(1944). He argued that there was no god, and no fixed standard of

conduct. Humans are “condemned to be free;” they have to choose their own

values and live by them, even though all their choices may be bad. In a world

without order one must to continue to move through it.

Camus discussed a

condition he called “absurd” in his essays. In his work there is an unbridgeable

gap between people’s hopes, goals, desires, and the irrational universe into

which they’ve been born. You wander through an irrational universe and

create what order you can. Camus expressed the “absurd” in novels,

stories, and essays, as well as a few plays, including Caligula (1945).

There was one major difference between absurdists and the

existential writers. Sartre’s and Camus’ plays were written with a

logical build in plot; their characters were relatively understandable as human

beings. “Absurdists” rejected logical plots and traditional

characters. If the universe and people’s lives are absurd, the plays

Absurdists wrote were chaotic in structure and characterization.

The three most important Absurdists were centered in Paris during

the late 1940s and early 1950s. The most important is

Samuel Beckett, whose Waiting for Godot, produced in 1953, won him international fame. Beckett was Irish, but he left his native country and exiled himself to France. Godot, along with other important early plays Endgame (1957) and Happy Days (1961), depicts people in some sort of afterworld, desolate and confusing. The characters do not

struggle to make logical sense of these worlds -- that would be impossible -- but to merely make it from one moment to the next, one day to the next. Nothing is clear, nothing makes sense, but in a darkly comic way (and these plays are very funny in places) they move (though some of them CAN’T move physically – see Winnie in Happy Days) through their lives. In a play CALLED Play, three people in urns tell their stories, heads only appearing as each speaks.

Samuel Beckett, whose Waiting for Godot, produced in 1953, won him international fame. Beckett was Irish, but he left his native country and exiled himself to France. Godot, along with other important early plays Endgame (1957) and Happy Days (1961), depicts people in some sort of afterworld, desolate and confusing. The characters do not

struggle to make logical sense of these worlds -- that would be impossible -- but to merely make it from one moment to the next, one day to the next. Nothing is clear, nothing makes sense, but in a darkly comic way (and these plays are very funny in places) they move (though some of them CAN’T move physically – see Winnie in Happy Days) through their lives. In a play CALLED Play, three people in urns tell their stories, heads only appearing as each speaks.

Eugene Ionesco was a Romanian

who settled in Paris. His first play, The

Bald Soprano (1950), he called an “anti-play.”

In it, and other early work, such as The Chairs (1952), he totally devalues and mocks language – the cliche-ridden, every-day jabber that most humans babble from day to day. Later plays, such as Rhinoceros (1960) and Exit the King (1962), show protagonists in a world of deadening conformity. Ionesco’s characters are more recognizable than are Beckett’s, because Ionesco targets the typical middle-class people that we bump into every day.

In it, and other early work, such as The Chairs (1952), he totally devalues and mocks language – the cliche-ridden, every-day jabber that most humans babble from day to day. Later plays, such as Rhinoceros (1960) and Exit the King (1962), show protagonists in a world of deadening conformity. Ionesco’s characters are more recognizable than are Beckett’s, because Ionesco targets the typical middle-class people that we bump into every day.

Jean Genet is the most rebellious of the three major

absurdists. For him, all that organized society has managed to do is to fail, and fail miserably. So Genet chose to revolt against society. He raged against traditional norms in order to achieve some kind of integrity. In his plays, such as The Maids (1947) and The Balcony (1956), Genet depicts life as an endless series of reflections in mirrors -- the “truth” can never be found.

The Absurdists were highly influential on other writers in Europe,

England and the United States: early Harold Pinter – The Dumbwaiter (1957); early Edward Albee – The Sandbox (1959) and The

American Dream (1960); and Arthur Kopit – Oh, Dad, Poor Dad, Mama’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feeling So Sad

(1960); in Czechoslovakia Vaclav Havel – The Garden Party (1963); and in Poland Slawomir Mrozek – Tango (1965) all have their roots in the

theatre of the absurd.

An important French playwright between 1945 and 1965 was Jean Anouilh (1910-1987). Not an absurdist, he wrote

instead in the literary mode. His primary theme had to do with maintaining integrity in a world that seems to have none. Anouilh wrote relatively light-spirited plays tinged with irony such as Ring Round the Moon (1947) in which a young dancer invited to a ball at a chateau faces a complicated, cynical world but is whisked off in a highly theatrical, fairy tale atmosphere to a happy ending. He wrote darker pieces as well, in which idealistic protagonists maintain their integrity at any cost, even if it means death, such as his adaptation of Antigone (1943). His version of the Saint Joan story, The Lark (1953), placed the young saint in the midst of a corrupt world dominated by dark political machinations. In Beckett (1960) the famous archbishop must choose between a life of compromise and certain death.

Theatre in the twentieth century has been labeled a director’s

theatre, as directors increasingly dominated the form. Jean-Louis Barrault, one of the finest actors in France, broke

from the Comédie Française shortly after the war, took several actors with him and formed his own company, where he focused on directing. Barrault blended smart mainstream ideas with the avant-garde by focusing on the words, at the same time noting that “the text of a play is like an iceberg, since only 1/8 is visible.” The director must complete the playwright’s text, revealing the rest by using all of theatre’s resources.

from the Comédie Française shortly after the war, took several actors with him and formed his own company, where he focused on directing. Barrault blended smart mainstream ideas with the avant-garde by focusing on the words, at the same time noting that “the text of a play is like an iceberg, since only 1/8 is visible.” The director must complete the playwright’s text, revealing the rest by using all of theatre’s resources.

Jean Vilar studied with

Barrault, and like his mentor he was a fine actor whose focus turned to

directing. In 1947 he started the important Avignon Festival, which is still going

strong today. In 1951 he took over the Théâtre National Populaire (TNP) and made it one of the strongest companies in France. The company made yearly tours to the regions of France. Vilar placed major emphasis on the actor, well lit and well costumed, with simple scenic elements, such as platforms and other set pieces. He believed that theatre should be available to all, ”a public service in the same way as gas, water, electricity.”

strong today. In 1951 he took over the Théâtre National Populaire (TNP) and made it one of the strongest companies in France. The company made yearly tours to the regions of France. Vilar placed major emphasis on the actor, well lit and well costumed, with simple scenic elements, such as platforms and other set pieces. He believed that theatre should be available to all, ”a public service in the same way as gas, water, electricity.”

Roger Blin worked in

small, out of the way spaces where avant-garde experiments were pursued.

He performed with Artaud in the 30s, and after World War II he became

associated with the theatre of the absurd. He directed the legendary

first production of Waiting for Godot,

as well as other plays by Beckett.

In the 1960s, France underwent a severe examination of conscience,

as did most other western nations. Roger

Planchon, from a working class background, responded in part by giving the

classics a fresh look. His productions seem to have been directed by a man who

has come to them on his own and not through the classroom. Planchon took over

the TNP in 1972 and mingled Brechtian and Artaudian techniques in an attempt to

make his productions of classics available and meaningful to the working

classes. The workers didn’t always get the message, alas, but Planchon’s

style was very influential throughout the western world.

Two more recent directors of influence in France are Patrice Chereau and Ariane

Mnouchkine. Chereau was for a time co-director with Planchon at the

TNP. Chereau used classics to comment on contemporary situations. He

directed Wagner’s Ring cycle in 1976,

attempting through it to show the debasement of values as a result of the

industrial revolution. He has worked in a number of different theatres in

France and throughout Europe. These two trends; conceptualizing classics

to speak to today’s world and traveling through Europe’s important theatres

imprinting his own style there, are perhaps the two most common themes in Chereau’s

work and in much European directing from the 70s forward. Chereau has recently

begun directing film as well. While not many stage directors make this move,

it’s becoming more common in Europe, Britain, and the U.S.

One of the French directors I most admire is Ariane Mnouchkine, whose Théâtre du Soleil has broken all sorts

of new ground. Her troupe is international: in 1990 it included actors from 21 countries. Mnouchkine specializes in western classics in non-western style productions. Her Richard II made use of Kabuki; her amazing Les Atrides set the story of Agamemnon’s wretched family in Kathakali dance style. In this way she works to link an increasingly intercultural world.

of new ground. Her troupe is international: in 1990 it included actors from 21 countries. Mnouchkine specializes in western classics in non-western style productions. Her Richard II made use of Kabuki; her amazing Les Atrides set the story of Agamemnon’s wretched family in Kathakali dance style. In this way she works to link an increasingly intercultural world.

Few recent French writers have been translated into English or

produced in English language theatres.

One notable exception is Yasmina

Reza (1959- ), whose plays have been

successful on stages throughout Europe, as well as in Britain and the United States. Her first international hit, Art (1994), deals with three friends’ reactions to an all-white modern painting that one of them has bought. In this comedy of manners, the age-old question “what is art?” is debated, but the men’s friendship is at the center of this play. In The Unexpected Man (1995), a man and a woman sit opposite each other on a train. He is a famous author, she an avid admirer who has one of his books in her bag. Will she open the bag? We find out through the inner mono-logues of the author and the fan. More recently God of Carnage has become an international success for her.

successful on stages throughout Europe, as well as in Britain and the United States. Her first international hit, Art (1994), deals with three friends’ reactions to an all-white modern painting that one of them has bought. In this comedy of manners, the age-old question “what is art?” is debated, but the men’s friendship is at the center of this play. In The Unexpected Man (1995), a man and a woman sit opposite each other on a train. He is a famous author, she an avid admirer who has one of his books in her bag. Will she open the bag? We find out through the inner mono-logues of the author and the fan. More recently God of Carnage has become an international success for her.

|

| Thomas Ostermeier's production of Nora (Ibsen's The Doll House) BAM Next Wave Festival 2004 |

Certainly the most important company after the war was Brecht’s

Berliner Ensemble. Bertolt Brecht

returned to Germany in 1947 and two years later, in the recently

partitioned east side (communist side) of Berlin, he opened the Berliner Ensemble with a production of Mother Courage. In 1954 the company moved to the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, where Brecht had had his greatest early success with Threepenny Opera, and where the Berliner Ensemble remains to this day. Brecht’s international reputation grew in the post war years, when three great plays,

Mother Courage, The Causasian Chalk Circle and The Good Person of Setzuan, written just before and during World War II were introduced to the world. The Berliner Ensemble, which featured the unique Brechtian style, became known as one of the world’s finest acting ensembles because the company toured, and theatrical practitioners visited Berlin to see the ensemble in action. The Brechtian style influenced many of the most famous directors and designers on the continent and in Britain. Brecht died in 1956, but his wife Helene Weigel ran the theatre for years after. The Berliner Ensemble remains an important theatrical entity today.

partitioned east side (communist side) of Berlin, he opened the Berliner Ensemble with a production of Mother Courage. In 1954 the company moved to the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, where Brecht had had his greatest early success with Threepenny Opera, and where the Berliner Ensemble remains to this day. Brecht’s international reputation grew in the post war years, when three great plays,

Mother Courage, The Causasian Chalk Circle and The Good Person of Setzuan, written just before and during World War II were introduced to the world. The Berliner Ensemble, which featured the unique Brechtian style, became known as one of the world’s finest acting ensembles because the company toured, and theatrical practitioners visited Berlin to see the ensemble in action. The Brechtian style influenced many of the most famous directors and designers on the continent and in Britain. Brecht died in 1956, but his wife Helene Weigel ran the theatre for years after. The Berliner Ensemble remains an important theatrical entity today.

The most important German-speaking writers of the 1950s were not

German, but Swiss. Max Frisch

wrote plays such as The Chinese Wall

(1946), which makes use of Brechtian

historification, set in a distant China during a masked ball. Characters such as Napoleon, Cleopatra, and Christopher Columbus comment on history, and a character named The Contemporary warns of an atomic bomb. In the darkly comic Biederman and the Firebugs (1958 - also called Arsonists) a town is plagued by arson, and yet Biedermann allows two suspicious strangers to stay in his attic. He even gives them matches. Thus Biedermann the victim becomes an accomplice in his own destruction.

historification, set in a distant China during a masked ball. Characters such as Napoleon, Cleopatra, and Christopher Columbus comment on history, and a character named The Contemporary warns of an atomic bomb. In the darkly comic Biederman and the Firebugs (1958 - also called Arsonists) a town is plagued by arson, and yet Biedermann allows two suspicious strangers to stay in his attic. He even gives them matches. Thus Biedermann the victim becomes an accomplice in his own destruction.

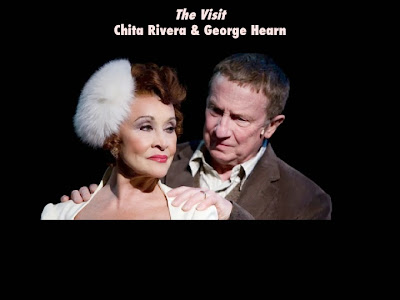

Like Frisch, Friedrich Dürrenmatt

focused on human weakness in face of moral dilemmas in grotesque, dark

comedies. His characters seem strong enough at first, but become

corrupted by power and wealth. In The

Visit a rich

old woman arrives in her hometown and offers a huge reward to

the entire town if any person in it will kill her former lover, now one of the

town’s most beloved citizens. He had impregnated her when they were very young,

and for this reason she moved away.

Surprise and anger on the part of the town’s loyal citizens soon turns

into greed, and by the end of the play, their former friend is dead. In The Physicists, a scientist named Möbius

has discovered a brilliant formula that could save the world or destroy it.

Knowing that the world is not ready for his formula, he places himself in an

asylum, where he encounters two other inmates who pretend to be mad, but who

are really secret service agents of two powerful countries, each assigned to

steal Möbius’ formula. Fräulein Doctor Hilde von Sant, the head of the asylum,

will not let them leave until SHE has the formula, and the power to control or

destroy the world. Rather than let her have it the men retreat back into

their “madness” as the curtain falls. In these plays the themes of guilt and

responsibility are quite apparent, and The

Physicists’ setting views the world as a madhouse.

|

| A musical version of The Visit, by Kander & Ebb |

Another way of dealing with German postwar guilt was to stage docudrama, which uses documents to

explore what has occurred in recent history. Rolf Hochhuth’s The

Deputy (1963) placed much of the blame for the extermination of the Jews on Pope Pius XII. By using speeches and other documents the author tried to show that the pope’s refusal to take a strong stand against Hitler was a major factor in the holocaust. The controversial play was banned in several countries. Another docudrama, Peter Weiss’s The Investigation (1965), used dialogues taken from the official hearings that studied the exterminations at Auschwitz as the basis of the action.

Deputy (1963) placed much of the blame for the extermination of the Jews on Pope Pius XII. By using speeches and other documents the author tried to show that the pope’s refusal to take a strong stand against Hitler was a major factor in the holocaust. The controversial play was banned in several countries. Another docudrama, Peter Weiss’s The Investigation (1965), used dialogues taken from the official hearings that studied the exterminations at Auschwitz as the basis of the action.

Peter Weiss wrote an even

more important play: Marat/Sade

(1964). The play is set in the asylum of Charenton in the year 1808 – the

inmates are putting on a

play written by fellow inmate the Marquis de Sade. De Sade’s play within a play is about Marat, hero of the French revolution. Weiss’s play examines Marat (political commitment no matter the price) vs De Sade (anarchy and sensuality as the only matters of importance). The most famous production of the play, directed in England by Peter Brook (1970), combined Artaud’s theatre of cruelty with Brecht’s Epic Theatre to create one of the most powerful productions in the late twentieth century. It was a highly influential piece of work too, impressing European and American directors.

play written by fellow inmate the Marquis de Sade. De Sade’s play within a play is about Marat, hero of the French revolution. Weiss’s play examines Marat (political commitment no matter the price) vs De Sade (anarchy and sensuality as the only matters of importance). The most famous production of the play, directed in England by Peter Brook (1970), combined Artaud’s theatre of cruelty with Brecht’s Epic Theatre to create one of the most powerful productions in the late twentieth century. It was a highly influential piece of work too, impressing European and American directors.

In the 1960s Austrian writer Peter

Handke (1942- ) outraged

traditionalists and delighted the younger generation in his first play, Offending the Audience (1966), in which

four actors enter, and explain to the audience that they will not

see a play tonight! They then mock traditional theatre, insult each other and the audience, and end by politely thanking the audience and bidding them a good night. This evening completely disregarded any established notion of what goes on in a theatre, and the result was a hilarious evening of what’s been called anti-theatre. Handke’s most famous play is Kaspar, which examines the socialization of Kaspar Hauser, kept in a closet from childhood, then released into the world, from which he retreats: a comment on the 20th century’s inability to be “civilized.”

see a play tonight! They then mock traditional theatre, insult each other and the audience, and end by politely thanking the audience and bidding them a good night. This evening completely disregarded any established notion of what goes on in a theatre, and the result was a hilarious evening of what’s been called anti-theatre. Handke’s most famous play is Kaspar, which examines the socialization of Kaspar Hauser, kept in a closet from childhood, then released into the world, from which he retreats: a comment on the 20th century’s inability to be “civilized.”

Heiner Müller (1929-1995)

took apart classical texts such as Medea

and Hamlet and radically cut,

reassembled and

combined the plays with other writings, fracturing old texts to create new, free-form prose poems for the stage. In Hamletmachine (1977), his most frequently produced work, Müller offers the audience compelling theatrical images that explore the plight of any committed Marxist to the revolution after the horrors inflicted in Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia in 1968. Müller also directed plays. From the mid-1990s until his death he was artistic director of the Berliner Ensemble.

combined the plays with other writings, fracturing old texts to create new, free-form prose poems for the stage. In Hamletmachine (1977), his most frequently produced work, Müller offers the audience compelling theatrical images that explore the plight of any committed Marxist to the revolution after the horrors inflicted in Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia in 1968. Müller also directed plays. From the mid-1990s until his death he was artistic director of the Berliner Ensemble.

To direct the work of Peter Handke or Heiner Müller requires a

bold, daring theatrical vision, and several German directors

took on this task fearlessly. The most important is Peter Stein (1937- ). He began his career in the mid-1960s and became associated with the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz in Berlin, where he developed a world-class company of actors. At this theatre he staged such diverse works as The Oresteia, As You Like It, and Chekhov’s Three Sisters. His deconstructions of classics gained him an international reputation. He has mellowed recently and directs at a number of important theatres, including the Moscow Art Theatre and The Edinburgh Festival. In the 1990s he was in charge of play production at the Salzburg Festival.

took on this task fearlessly. The most important is Peter Stein (1937- ). He began his career in the mid-1960s and became associated with the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz in Berlin, where he developed a world-class company of actors. At this theatre he staged such diverse works as The Oresteia, As You Like It, and Chekhov’s Three Sisters. His deconstructions of classics gained him an international reputation. He has mellowed recently and directs at a number of important theatres, including the Moscow Art Theatre and The Edinburgh Festival. In the 1990s he was in charge of play production at the Salzburg Festival.

Other German directors have continued to push the bounds of the

theatrical experience in their work. Claus

Peymann (1937- ) directed Handke’s and Müller’s plays, as well as the plays

of Thomas Bernhardt. Peymann worked for more than

ten years at the Burg-theater in Vienna, making it one of the finest ensembles in the world. Frank Castorf (1951- ) rejoices in shocking audiences, and has subjected some of the greatest writers, including Shakespeare and Tennessee Williams, to radical, irreverent re-workings at the Volksbühne in Berlin, which he has managed since 1990. Also in Berlin, Thomas Ostermeier (1968 - ) made his

reputation at the experimental wing of the Deutsches Theater, and now runs the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz. Ostermeier gained his reputation directing cutting edge work by young playwrights, including radical British writers Mark Ravenhill and Sarah Kane. He also updates the classics. His production of Nora (Ibsen’s Doll’s House) is set in a posh Berlin neighborhood in the twenty-first century. In it, Nora is driven to desperate measures – she walks out the door at the end, but returns & empties a pistol into her husband Torvald. Ostermeier updated Hedda Gabler as well – Lovborg’s manuscript? A laptop.

ten years at the Burg-theater in Vienna, making it one of the finest ensembles in the world. Frank Castorf (1951- ) rejoices in shocking audiences, and has subjected some of the greatest writers, including Shakespeare and Tennessee Williams, to radical, irreverent re-workings at the Volksbühne in Berlin, which he has managed since 1990. Also in Berlin, Thomas Ostermeier (1968 - ) made his

reputation at the experimental wing of the Deutsches Theater, and now runs the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz. Ostermeier gained his reputation directing cutting edge work by young playwrights, including radical British writers Mark Ravenhill and Sarah Kane. He also updates the classics. His production of Nora (Ibsen’s Doll’s House) is set in a posh Berlin neighborhood in the twenty-first century. In it, Nora is driven to desperate measures – she walks out the door at the end, but returns & empties a pistol into her husband Torvald. Ostermeier updated Hedda Gabler as well – Lovborg’s manuscript? A laptop.

Pina Bausch (1940-2009) created an art that breaks the barriers between theatre and dance At her Tanztheater

No comments:

Post a Comment