all sorts of plays from this period have been revived. One playwright, however, towers above the others of this period, and that man is Eugene O'Neill. He wrote several plays that are still produced regularly today, and he wrote several others that may never get another production! What is perhaps most important about this giant is that he read the great Europeans assiduously, and constantly experimented with different forms. Whether he failed or succeeded, his experiments encouraged other Americans not only to write, but also to be unafraid of experimenting in their own ways.

O’Neill started with realistic one-acts about the sea. He

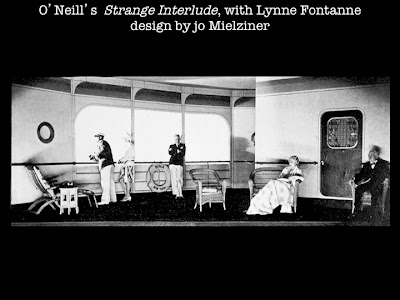

used the techniques of Pirandello in his play Lazarus Laughed

(1925-26). In Strange Interlude (1926-27) the characters spoke their inner thoughts as well as their words. He modeled Mourning Becomes Elektra (1929-31) after the Oresteia, updating it to the American Civil War. And he used the Hippolytus/Phaedra legend as the basis for Desire Under the Elms (1924). He used expressionist techniques in several plays, most notably in The Hairy Ape (1921). And his last

plays move into a sort of symbolist-poetic realism. Long Day’s Journey into Night (1939-41) and The Iceman Cometh (1939) are the best of these. As already noted, O’Neill did not succeed in all his experiments, but his attempts were often brilliant in themselves, and also empowered those who came after him. He won four Pulitzer Prizes (Beyond the Horizon, Anna Christie, Strange Interlude and Long Day’s Journey), the only writer thus far to have done so, and he is still the only American playwright to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

(1925-26). In Strange Interlude (1926-27) the characters spoke their inner thoughts as well as their words. He modeled Mourning Becomes Elektra (1929-31) after the Oresteia, updating it to the American Civil War. And he used the Hippolytus/Phaedra legend as the basis for Desire Under the Elms (1924). He used expressionist techniques in several plays, most notably in The Hairy Ape (1921). And his last

plays move into a sort of symbolist-poetic realism. Long Day’s Journey into Night (1939-41) and The Iceman Cometh (1939) are the best of these. As already noted, O’Neill did not succeed in all his experiments, but his attempts were often brilliant in themselves, and also empowered those who came after him. He won four Pulitzer Prizes (Beyond the Horizon, Anna Christie, Strange Interlude and Long Day’s Journey), the only writer thus far to have done so, and he is still the only American playwright to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

After O’Neill, a wide range of writers emerged in this era, and some of them are still widely produced. Elmer Rice (1892-

1967) wrote both the expressionistic Adding Machine (1923) and the realistic Street Scene (1929), two very different cries against injustice. Sidney Howard (1891-1939) wrote in a number of genres. His play They Knew What They Wanted not only won the Pulitzer Prize in 1924, but also was turned into Frank Loesser’s musical Most Happy Fella in 1956.

Three of the finest writers produced by the Theatre Guild were Maxwell Anderson (1888-1959), Robert Sherwood (1896-1955) and William Saroyan (1908-1981). Anderson

dared to write blank verse dramas such as Mary

of Scotland (1933), as well as gritty prose anti-war pieces such as What

Price Glory (1924). Sherwood’s prophetic play Idiot’s Delight (1936) showed, in tragicomic terms, a world on the brink of disaster. The play is set in a European hotel on a mountaintop from which can be seen four countries. A varied, interesting collection of people gather in the hotel, including an American hoofer and his troupe of young dancing girls, and a mysterious woman of supposed Russian nobility. In the end, as the hoofer and the Russian reach out to each other, war begins. When, similar to Shaw’s

Heartbreak House, explosions surround the hotel, the curtain falls. Saroyan set his best play, The Time of Your Life (1939), in a seedy bar. Its denizens include a champagne-drinking philosopher, a sad hooker, a would-be comic who can’t tell a joke, but happens to tap dance terrifically, and a pathological liar who calls himself Kit Carson. These, tragicomic types take refuge in the bar against oppressive, authoritarian forces, in a play that manages to be very funny and very sad at the same time.

Price Glory (1924). Sherwood’s prophetic play Idiot’s Delight (1936) showed, in tragicomic terms, a world on the brink of disaster. The play is set in a European hotel on a mountaintop from which can be seen four countries. A varied, interesting collection of people gather in the hotel, including an American hoofer and his troupe of young dancing girls, and a mysterious woman of supposed Russian nobility. In the end, as the hoofer and the Russian reach out to each other, war begins. When, similar to Shaw’s

Heartbreak House, explosions surround the hotel, the curtain falls. Saroyan set his best play, The Time of Your Life (1939), in a seedy bar. Its denizens include a champagne-drinking philosopher, a sad hooker, a would-be comic who can’t tell a joke, but happens to tap dance terrifically, and a pathological liar who calls himself Kit Carson. These, tragicomic types take refuge in the bar against oppressive, authoritarian forces, in a play that manages to be very funny and very sad at the same time.

Clifford Odets (1906-1963) has

been mentioned as a member of the Group Theatre, and though he wrote for

Hollywood as well, the theatre has the best of his work, in powerfully realistic plays that made use of a uniquely poetic language of the people, and that usually featured an angry young man at the center of the action. Waiting for Lefty (1934), about a taxicab strike in New York, was a play written in short jabbing scenes, dashed off by Odets in a matter of days. It ended with the words “Strike! Strike!” shouted out by the actors, and on its first night the

audience rose to its feet and joined the players’ outcry. After this success, Odets penned Awake and Sing (1935), a play about lower-middle class Jews in the city struggling to break free of the tenement life they inhabited. And as he left for Hollywood, his play about an Italian American boxer, called Golden Boy (1937), produced the greatest success of the Group Theatre.

Hollywood as well, the theatre has the best of his work, in powerfully realistic plays that made use of a uniquely poetic language of the people, and that usually featured an angry young man at the center of the action. Waiting for Lefty (1934), about a taxicab strike in New York, was a play written in short jabbing scenes, dashed off by Odets in a matter of days. It ended with the words “Strike! Strike!” shouted out by the actors, and on its first night the

audience rose to its feet and joined the players’ outcry. After this success, Odets penned Awake and Sing (1935), a play about lower-middle class Jews in the city struggling to break free of the tenement life they inhabited. And as he left for Hollywood, his play about an Italian American boxer, called Golden Boy (1937), produced the greatest success of the Group Theatre.

Comedy thrived in the years between the wars. Philip Barry (1896-1949) specialized in

an American comedy of

manners, one of his best plays, The Philadelphia Story, (1939) dealing with love and divorce among the upper classes. George S. Kaufman ((1889-1961) partnered with a number of writers, in fact he wrote only one play on his own. He found his finest match with Moss Hart (1904-1961). Their two comedies You Can’t Take it With You (1936) and The Man Who Came to Dinner (1940) have been revived regularly in summer stock productions as well as on Broadway and in regional theatre.

manners, one of his best plays, The Philadelphia Story, (1939) dealing with love and divorce among the upper classes. George S. Kaufman ((1889-1961) partnered with a number of writers, in fact he wrote only one play on his own. He found his finest match with Moss Hart (1904-1961). Their two comedies You Can’t Take it With You (1936) and The Man Who Came to Dinner (1940) have been revived regularly in summer stock productions as well as on Broadway and in regional theatre.

Many American women wrote plays in this era. Susan Glaspell (1876-1948) wrote Trifles (1916) and other pieces

for the Province-town Players, which group she helped to found. She won a Pulitzer Prize for her 1931 play, Alison’s House. The first woman to win a Pulitzer was Zona Gale (1874-1938) for the play Miss Lulu Bett (1920). Rachel Crothers (1876-1958), whose first Broadway effort was The Three of Us (1906), wrote many successful plays. She

directed many of the plays she wrote, including, Susan and God (1937), thus retaining an unusual amount of control over production of her work. Edna Ferber (1885-1968) adapted her novel, Showboat, into the important musical of that name. She was a frequent writing partner of George S. Kaufman, most notably in The Royal Family (1927), a spoof on the Barrymore family that is frequently revived, and Stage

Door ((1936). Sophie Treadwell (c.1885-1970) wrote the expressionist Machinal (1928), which tells of a woman who is driven to murder by the machine-like world she lives in. Edna St Vincent Millay was a poet/playwright and a bit of a femme fatale. In 1924 she founded the Cherry Lane Theatre in Greenwich Village which is still alive and kicking today, and

wrote several plays, one of which, Aria da Capo, Dr Jack was in, in the deep dark past. Of the women writers, one is as well remembered as the best male playwrights of the era, and that woman is Lillian Hellman (1905-1984). Her The Children’s Hour (1934) both shocked and fascinated Broadway audiences with the accusations by a mean-spirited girl that her two teachers are in a lesbian relationship. And her plays of greed and power in the American South, most notably The Little Foxes (1939), are performed regularly and still resonate strongly today.

Finally, Thornton Wilder (1897 -- 1975) was among the strongest writers just before World War II, and remains one

of the most produced American playwrights today. Wilder experimented with several European styles to create the uniquely American Our Town (1938). During the dark days of the Second World War he showed how humans have managed to pull through disaster after disaster, if only by The Skin of Our Teeth (1943). And his re-working of Austrian Johann Nestroy’s Out for a Lark, as I have already noted more than once for its unique theatrical genealogy, yielded The Merchant of Yonkers, re-worked as The Matchmaker. That play was transformed in the 1960s into the blockbuster musical Hello, Dolly!

African American theatre took a series of giant steps forward during this period. One author of African-American theatre history characterized the movement as progressing

such as vaudeville star Bert Williams (1876-1922) were still forced to “black up,” applying burnt cork to their faces for their acts, by the 1920s the Harlem Renaissance had begun to empower Black theatre. As early as 1915 actress Anita Bush (1883-1974) created a stock company that grew into the important Lafayette Players. This group lasted until 1932, and which was responsible for training a large number of Black actors. African American musicals had played Broadway since

the turn of the century, when In Dahomey, written by and starring Bert Williams and George Walker, proved a hit. In 1921 Noble Sissle (1889-1975) and Eubie Blake (1883-1983) wrote Shuffle Along, and this hit sparked a series of other African American musicals. White writers began to break away from caricature and stereotype at this time in their depiction of Blacks on stage, but more importantly,

significant pieces for the theatre began to be written and performed by Black writers. As early as 1916, Angelina Grimke (1880-1958) wrote Rachel, which had a production that year in Washington D.C., and the following year in New York City’s Neighborhood Playhouse, as well as in Cambridge Massachusetts. The first serious play by a Black to be produced on Broadway was The Chipwoman’s Fortune, in 1923, by Willis Richardson (1889-1977). Perhaps the most powerful African American play of the time was Langston Hughes’ Mulatto (1935). Hughes also teamed with Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) to write Mulebone in 1931.

In the area of performance, Charles Gilpin (1878-1930) created a sensation as O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones (1920).

Jack Carter (c. 1902-1967) played a Black Mephistopheles to Orson Welles‘s Dr. Faustus, and also played the title role in the Federal Theatre Project’s Voodoo Macbeth. Josephine Baker danced in the Zeigfeld Follies before she left the United States for better professional opportunity and personal life in Paris. In Paris she was acclaimed and became almost legendary in stature. In the 1926 revival of The Emperor Jones, an actor named Paul Robeson (1898-1976)

took the role, and he also made the film versions of that play and Showboat. Robeson is certainly one of the most important stage actors between the wars, and he became the first African American ever to play Othello on Broadway, in 1943. The production featured Jose Ferrer as Iago and the legendary Uta Hagen as Desdemona. Robeson, as well as being a consummate performer, was also an activist, fighting fearlessly for political and social rights. His political stance caused him trouble with the U.S. Government throughout his life.

The American

musical made great strides in the period between the wars. The Ziegfeld Follies (1907-1931) upheld

the tradition of long-legged, scantily clad women backed by lots of music and spectacular scenery, but changes in the form began slowly to occur. As early as 1904, George M. Cohan (1878-1942) wrote and starred in a show named Little Johnny Jones, which featured more of a plot than was usual in a musical as well as two famous songs, Give My Regards

to Broadway and I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy. The European operetta also exerted an influence on the musical, offering new and often relatively serious musical melodramas. American composer Jerome Kern (1885-1945) created relatively intimate musicals at the Princess Theatre, with comic plots on uniquely American themes. An example of this new style is the “collegiate” musical, Leave It to Jane (1917), in which a college president’s daughter is persuaded to flirt with a football star to keep him from transferring to another school, but who falls in love with him instead.

the tradition of long-legged, scantily clad women backed by lots of music and spectacular scenery, but changes in the form began slowly to occur. As early as 1904, George M. Cohan (1878-1942) wrote and starred in a show named Little Johnny Jones, which featured more of a plot than was usual in a musical as well as two famous songs, Give My Regards

to Broadway and I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy. The European operetta also exerted an influence on the musical, offering new and often relatively serious musical melodramas. American composer Jerome Kern (1885-1945) created relatively intimate musicals at the Princess Theatre, with comic plots on uniquely American themes. An example of this new style is the “collegiate” musical, Leave It to Jane (1917), in which a college president’s daughter is persuaded to flirt with a football star to keep him from transferring to another school, but who falls in love with him instead.

Then, in December 1927, a musical called Showboat, based on Edna Ferber’s novel, with music by Jerome Kern and

lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein, surprised the nation. It attempted to tell a very serious love story, as well as to deal with the issue of race, in the case of a major character “white enough to pass.” This show changed the course of American musical theatre. Showboat was followed by a wave of brilliant songs and clever books for new American musicals. George (1898-1937) and Ira (1896-1983)

Lawrence, as well the great American folk opera, Porgy and Bess (1935). In 1931 the Gershwin brothers also produced the first musical to win a Pulitzer Prize, Of Thee I Sing. Cole Porter (1891-1964) wrote The Gay Divorce (1932), which starred Fred Astaire, and Anything Goes (1934), which featured Ethel Merman, along with a host of other clever musicals. The team of Richard Rodgers (1902-1979) and Lorenz Hart (1895-1943), created some of

the great musicals of the 1930s, including On Your Toes (1936) Babes in Arms (1937), The Boys from Syracuse 1938), and Pal Joey (1940). Irving Berlin (1988-1989) wrote numerous songs for revues, notably the Zeigfeld Follies and his own Music Box Revues at the theatre of that name during the 1920s, and songs for films as well in the period between the wars, but almost immediately after the war wrote Annie Get Your Gun, which has proved a very durable musical indeed.

We’ve already noted that, with the rise of the talking motion

picture, stage actors were often lured out to Hollywood, and many never

returned. Frequently, however, actors performed in both films and on

stage. In the era between World War I and World War II the theatre began to

move away from being a truly “popular” entertainment, becoming displaced by

motion pictures. Thus the 1930s was an

interesting and often quite difficult time of transition, particularly for performers.

The Barrymores were the

leading family in the theatre during the years between the wars, in fact

Kaufman and Ferber dubbed them the “royal” family in their comedy which

only loosely disguised John (1882-1941), Ethel (1879-1959), Lionel (1878-1954), and others of that distinguished acting clan. Lionel Barrymore was the oldest, and was better known on film than on stage, most memorably in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life in 1946, playing the role of Mr. Potter the banker. John Barrymore was the leading American Shakespearean actor in the 1920s, reaching the apex of fame in his 101 nights Hamlet. Ethel played many roles on stage, making her Broadway debut in Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines (1901), and preferred the stage to film. Later in her life, however, she played in several major motion pictures.

only loosely disguised John (1882-1941), Ethel (1879-1959), Lionel (1878-1954), and others of that distinguished acting clan. Lionel Barrymore was the oldest, and was better known on film than on stage, most memorably in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life in 1946, playing the role of Mr. Potter the banker. John Barrymore was the leading American Shakespearean actor in the 1920s, reaching the apex of fame in his 101 nights Hamlet. Ethel played many roles on stage, making her Broadway debut in Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines (1901), and preferred the stage to film. Later in her life, however, she played in several major motion pictures.

Several other important actors we have already discussed,

including Orson Welles, Eve Le Gallienne and Paul Robeson. Le Gallienne had

limited interest in film, and had rather little success in it. Robeson’s stage career was more distinguished

than his film career, though in film he fared better than any other African

American, most of whom were relegated to embarrassing stereotyped servant

roles. Welles, on the other hand, left the world of theatre for film, and never

looked back, except to film plays of Shakespeare on several occasions. He

brought actors with whom he had worked in the Mercury Theatre to Los Angeles,

most notably Joseph Cotten, who made

a fine career in the movies. The actors from the Group Theatre, who included

Franchot Tone, John Garfield, and Frances Farmer, made their careers in

Hollywood, as well, primarily because the “method” taught them by Lee Strasberg

was intimate, based on inner emotions, and more suited to film than the larger,

gesticulating style used by most stage actors of the era. One of the most

talented actresses of the era was Katherine

Hepburn (1907-2003), whose career began on stage, and though she

occasionally returned to it, she is much better remembered for a lifetime of

brilliant screen performances.

The most successful couple on the American stage was the great

team of Alfred Lunt (1893-1977) and Lynne

Fontanne (1887-1983). They performed in the original production of Design for Living, starring alongside its author, Noel Coward. They also played Shakespeare, important European plays such as Ference Molnar’s The Guardsman, and Jean Giraudoux’s Amphitryon 38, as well as new American plays, including Idiot’s Delight.

Fontanne (1887-1983). They performed in the original production of Design for Living, starring alongside its author, Noel Coward. They also played Shakespeare, important European plays such as Ference Molnar’s The Guardsman, and Jean Giraudoux’s Amphitryon 38, as well as new American plays, including Idiot’s Delight.

One of the most popular actresses in the early years of the 20th

century was Laurette Taylor

(1884-1946), but after a tremendous success in light, long running comedies

such as Peg O’ My Heart (1912), she

turned to alcohol after her husband’s death in 1928. She returned in

triumph to the stage in 1945, as the original Amanda in The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams, but died soon after.

Two other actresses had long, successful careers, and chose the

stage over film. The diminutive Helen Hayes (1900-1993), who has often

been called “the first lady of the

American Theatre,” had a wide range, but was at her best in playing monarchs such as Mary Queen of Scots (1930), and Victoria Regina (1935). Catherine Cornell (1898-1974) was at ease in romantic leads as well as in character roles. She made her debut with the Washington Square Players, played Elizabeth Barrett in The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1931) and the title role in the American premiere of Shaw’s Candida (1924). She was a tireless touring star, and perhaps one of the last of them. Many Americans saw Cornell’s work on these tours, and she often brought them classical plays, most frequently Shakespeare, as well as modern works.

American Theatre,” had a wide range, but was at her best in playing monarchs such as Mary Queen of Scots (1930), and Victoria Regina (1935). Catherine Cornell (1898-1974) was at ease in romantic leads as well as in character roles. She made her debut with the Washington Square Players, played Elizabeth Barrett in The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1931) and the title role in the American premiere of Shaw’s Candida (1924). She was a tireless touring star, and perhaps one of the last of them. Many Americans saw Cornell’s work on these tours, and she often brought them classical plays, most frequently Shakespeare, as well as modern works.

We’ll return to the U.S. to see what happened to theatre there after

the Second World War, but next time we’ll look at Europe after 1945.

Casino (Salon, AR) - Mapyro

ReplyDeleteCasino (Salon, 아산 출장샵 AR) · 3.0 (0) · 4.1 (10) · 5.0 제천 출장마사지 (15) · 6.0 (11) · 광주 출장안마 7.0 (15) · 8.0 남양주 출장샵 (15) · 9.0 (9) · 10.0 (13) · 16.0 (15) · 경산 출장마사지 Blackjack (Salon, AR) · 18.1 (12) · 13.5 (7) · 21.1 (12)